The first time I visited this place, I went there for much the same reason that I head to most places – I noticed the green hilly thing and wanted to see what interesting paths it held. That first visit was followed quite quickly by another, then another, and I’ve kept going back every now and then. It’s a really neat little spot. In much the same way that I was drawn to this raised spot of land standing out from the surrounding flatness, humans have been drawn to this hill for thousands of years, and the end result is that in a gentle 2km wander, you can get a crash course in the geography, culture, politics and history of Taiwan.

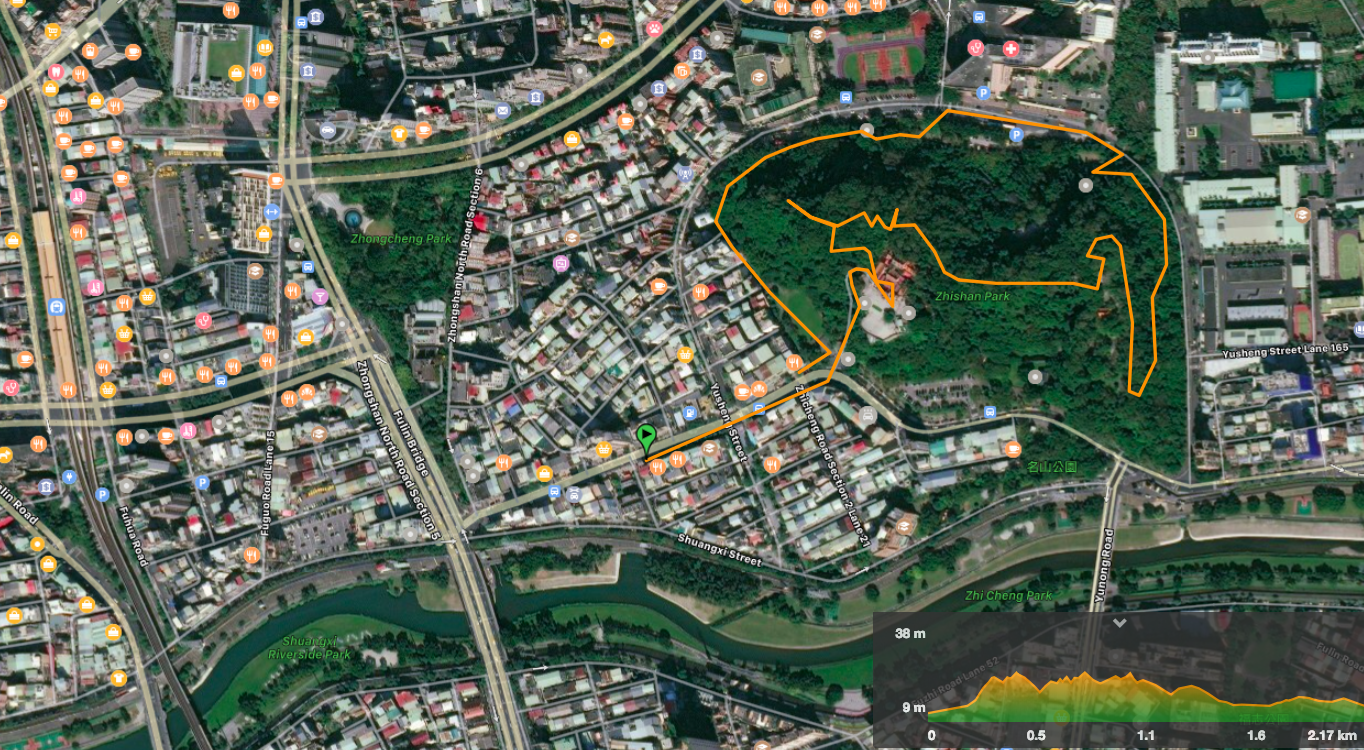

Distance: 2.2km

Time: 1 hour – at a super slow speed. Actually though, I think you could spend a lot longer here, (especially if you can read Chinese, or have a friend who can), because there a whole lot of historical sites and things of interest to learn about.

Difficulty: 1/10 – the steps up to the temple are steep, but short, after that most of the track is an undulating wooden walking.

Total ascent: 80m – the hill only rises about 52m above sea level.

Water: whatever you’d normally carry for a walk in the city. Inside the temple (to the right as you walk in), there are a couple of water machines and a teapot full of tea that visitors can use. I went up the steps with an empty water bottle and came down with a fuller one.

Shade: pretty well shaded, but I’ve taken an umbrella in the sun.

Mobile network: clear throughout.

Enjoyment: hiking–wise this isn’t worth mentioning, but for a glimpse into Taiwan’s past it is an excellent way to spend a morning or afternoon.

Other: if you can’t read Chinese, I highly recommend that you bribe a local friend to take you – you’ll get a lot more out of it if you can work out what you’re looking at.

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map, GPX file, and transportation information.

A grand paifang stands over the steps that will start your journey through many layers of Taiwan’s history. It is one of several routes up to the top, but it is my preferred starting point because going up this way, you get to make eye contact with all of the stone lions which guard the steps.

As you walk up from the road, you are welcomed by statues flanking the imposing grey steps. Numbers etched onto the surface tell you how far you have already climbed. On the right, there are the 18 Arhats – the enlightened followers of the Gautama Buddha who have been tasked with guarding the Mahayana Buddhist faith.

Perhaps I am not a very good person, but I read their expressions as ranging from bored to stoned through enraged, delirious and foolish. However, having researched more of their backstories I found out that I was just lacking the enlightenment to see their expressions for what they really are: joy, contentment, gentle power, jubilation, dignity and easy comfort.

Once you have climbed past the 18 Arhats, you find yourself standing at an old stone gate. In fact, this was originally one of four gates positioned to the north, east, south and west points of fortifications encircling the top of Zhishanyan. These defences were built in 1825 by settlers from Zhangzhou (漳州), who had claimed the land. The people that they were using the walls and gates to defend against were likewise Fujian settlers, but from Quanzhou (泉州). The crenelated walls are punctuated by loopholes for more aggressively defending the inner courtyard with weapons. It’s a pretty unique structure for Taiwan, and as such has been granted some form of protected status. It is also now the sole remaining section of the defensive structures from this period. Just outside the gate there is a giant camphor tree which leans out over the hill – the people responsible for managing the site are worried that what with the soil erosion that the area is suffering from, it wouldn’t be impossible for a typhoon or earthquake to tip the tree, and consequently destroy the gate.

If you look up to the left after passing through the gate, you can spot the Snake and Frog Stones (蛇蛙石), so named because it apparently resembles these two animals. I wasn’t certain, but I think the smaller one which looks like it’s about to get eaten by the bigger snake must be the frog. In total there are actually four stone animals who guard this mound – the ‘four great diamonds of Zhishanyan’ – the snake, a lion, an elephant and a horse, (frogs don’t make good guard animals I guess). I have only ever spotted the snake and the elephant rocks on my visits – maybe I wasn’t paying close attention.

At the very to of the steps you find yourself standing next to Huiji Temple. The current iteration of the temple dates back to 1968 (there have been five rebuilds since it was first constructed in the 1750s-60s).

The main front hall of the temple is dedicated to Sage King Chen (聖王公), a military leader-cum-daoist-deity that Fujian settlers brought over with them when they crossed the Taiwan Strait. An upper hall houses Wenchang Gong – another daoist god with connections to Fujian, (this one is associated with scholarly pursuits), and there is also a Buddhist deity in the lower hall.

The forecourt has views over Shilin, and there has been a temple cat on two of the occasions when I’ve visited.

Paths lead off into the trees to both sides of the temple, but on this route, I headed back towards the steps I’d entered through, and then off up the trail just beyond the arch.

Turn left where the path hits a T-junction. Both paths arrive at the same spot, but the left one is longer and more interesting.

Looking to the sides of the trail will bring you face-to-face with some of the more recent ghosts who used to inhabit this small hill. Here a concrete sentry sits camouflaged amongst the trees which are slowly reasserting their claim to the space. There are a couple such structures up here and they, along with with the other military traces (there are also ammunition stores and air raid shelters up here but I either didn’t notice them or didn’t pass that way) are actually the most recent marks on the landscape of the place.

During Taiwan’s period of martial law this location’s natural geography lent itself to being a defensive vantage point. From up here, soldiers had a clear view south out over Chiang Kai-Shek’s Shilin Official Residence. Guards stationed at Zhishanyan protected Taiwan’s former president for the 26 years that he lived in the building, and also used the position to help maintain law and order in the larger Shilin District.

Large trees everywhere sprawl and spread their roots and limbs wherever they please. Some are Chinese banyans, some are camphor trees, and there are also longan trees and acacias.

At this lovely specimen, you can head left to go to the lookout point, (next photo) then come back. The flat portion of land just left of the large tree contains many plaques laid into the floor detailing aspects of Taiwan’s geographical, cultural and military history (in Chinese).

At the end of a raised walkway sits a concrete gun emplacement – back when there was a military camp stationed here, this was the westernmost defensive vantage point. I can only assume that in previous years, the trees here was smaller, since now it would be a little hard to defend from here. There are information boards ranged around a model of Taipei – the boards all describe the geological forces that have shaped the landscape of Zhishanyan and the wider Taipei basin around it. Some talk about volcanic activity in the region, one outlines how tectonic plate movements have raised certain areas, another explains the features which make the land here prone to flooding. As with pretty much all the information here, it would be great if they were bilingual so that it was possible to understand more.

After returning back to the path where I’d came from, I headed left to continue the loop.

There are more signs, one indicating fossils in the rocks which, despite being many metres above sea level now, must have originally come from the seabed. And there are more remains of last century’s military presence.

The raised wooden walkway comes down close to the old north gate of the Zhangzhou settler’s protected area, (just downhill to the left of the frame). Not much remains of their handiwork, however if you walk to the northernmost point of the paved area behind Zhishanyan Pavilion you can spot a more recent historical mark.

Right in the corner, boxed in by subsequently installed fencing is an elegant Japanese shrine. The style is strikingly different to the brightly coloured Daoist look that’s more common here. Bizarrely, this seems to be the only feature which doesn’t have an information board explaining it in detail, (or maybe it does and I just didn’t spot it). From later research online, it seems that this was a shrine built by the Japanese to worship O-Jizo-Sama, (in Chinese 地藏王/Di Zang Wang), a much loved bodhisattva who protects travellers, children who die whilst still young, as well as those who die as a result of miscarriage or abortion. Although there is no longer a statue of O-Jizo-Sama residing at the shrine, it seems that there are still a few people around who come to worship here–the last time I visited someone had placed sweets upon the stone table.

To continue the walk along the top of the hill, take the trail which heads behind Huiji temple (the one which leads back to the temple will be on your right as you face the ‘correct’ path). Here more signs tell you of various natural features including the elephant rock which you can find off a brief detour on the left.

Continuing a little further, you pass some physical reminders of some of this place’s tragic past. (Undoubtedly, there are political components to the events that unfolded which I can only partially comprehend, however on a human level, the events that happened were terrible.) To the left of the trail there are several small gravestones and behind them a memorial stone. These are markers left to remember the deaths of the six Japanese teachers who were killed in the 1896 ‘Zhishanyan Incident’. At that time, Taiwan was under Japanese rule, and in order to better control the Taiwanese population, the Japanese powers decided to make Japanese the national language of Taiwan. The first step in achieving that was to bring over teachers and set up a Japanese language training institute where Taiwanese children could be instructed in the new language. The location they chose as their new base for promoting Japanese education was the Huiji Temple. Not even a full year after the school was established, a local group of resistance fighters from Zhilanbao, (an old administrative region that includes most of modern-day Shilin and Neihu Districts and well as parts of Beitou and Zhongshan), attacked the school and killed six teachers.

After the attack, some of the teachers’ ashes were put to rest here on Zhishanyan. In 1903, the site became a more general shrine for the remembrance of educators, (台灣亡教育者招魂碑), and a stone tablet was installed and inscribed with the names of many teachers. Later still, in 1929, a shrine was built for the six teachers who had been killed.

As a further testament to Taiwan’s frequently sad and complicated past, the monument and stone tablets that you will see if you visit today are not the ones that were installed at the time because the originals were destroyed when the KMT government took charge of Taiwan after World War Two. What you see today were only placed there in 2001 after the military protection on Zhishanyan was lifted.

As if six murdered teachers wasn’t enough unpleasantness, just a short way along from their monument you will find a small land god shrine and a large grave. Unlike most similar structures around Taiwan, you can’t find a family name here, instead, a close look will reveal ‘同歸所’ picked out in gold letters behind the candles and incense sticks. That is because this is a mass grave for all the unknown and unclaimed victims of the 1786 Lin Shuangwen rebellion. The Lin Shuangwen rebellion was one of many rebellions and uprisings in the early Qing Dynasty, and in this particular event, many fighters on the Zhangzhou side were trapped upon Zhishanyan and killed by the opposing Quanzhou and Chinese government forces.

Continuing on along the path you will arrive at this junction. The large tree just out of frame to the left is a camphor tree which is claimed to be over 300 years old. It is strange to imagine the tree sitting there and observing all the battles and changes that have played out over the land here.

Just behind the tree is a reading room – as far as I can establish, it was set up on the first site of the shrine for the teachers killed in the Zhishanyan incident. The reading room was built when that original shrine was destroyed and is still in use today. Benches are set up like classrooms, books fill a couple of bookcases, and large posters describing the history of the area decorate the walls.

Turn left here to cover the whole of the path.

The path climbs a little and passes the reconstructed stone tablets made by the Japanese to commemorate old teachers. The smashed remains of the original stones have been left in place and are still visible on the ground – an interesting, thoughtful way of acknowledging the many historical and political lenses through which Taiwan has been viewed.

If you follow the trail to its apex, you will find yourself at the highest point of Zhishanyan. Here the trees part to give you a view of Taipei City Yangmingshan Hospital. On one visit, I was struck by the sight of a temple in the hospital’s courtyard; my friend casually said, that of course there is a temple in every hospital here, the same way there is a chapel in the UK. After she said that, it made perfect sense, I had just never considered that before.

The trail leads back down the other side of the stone tablets and reading room, both on the right of the path. There is a toilet block here, and a large pavilion that always seems to have someone feeding the cats and squirrels which congregate around in and around the trees.

If you head straight you will come to a plaza with some steps heading straight down and paths leading to the left. The straight-down steps are another feature left from the period of Japanese occupation – steps seem to be a common feature of Japanese sites of worship, (I couldn’t find any information as to why this might be, so if anyone knows, please feel free to enlighten me).

I wanted to double back and explore the lower region of the hill though, so I took the winding wooden path snaking down to the left.

To cover the drop in elevation smoothly, the path zigzags downwards until it becomes more-or-less level with the road. I really like these paths that have been constructed all over Zhishanyan, not only do they protect the soft sandstone and historical remains, but they also allow access for people who would struggle with steps.

The path heads both ways around the base of the hill, I kept walking anti-clockwise.

The path terminates near the hospital and you have to walk along the road for a way.

The path restarts a little beyond the hospital, and this section draws attention to the area’s oldest known inhabitants. If you look up your right, you might spot the Shilin Elementary School, and whilst the buildings there now are quite modern, the has housed educational establishments dating back until the 1890’s. As you may realise from the date, this discovery happened during the period of Japanese rule – many Japanese experts in a variety of fields were sent over to study, survey and document the land, and it was one of these surveys which led to the revealing of what has become known as Taiwan’s ‘Zhishanyan Culture.’

There are several distinct prehistoric cultures that have existed in Taiwan from 20,000-30,000 years ago up until the arrival of Dutch traders marked the start of Taiwan’s recorded history in the 1600’s. (If you like this sort of thing, perhaps you’d enjoy a trip to the Shihsanhang Museum of Archaeology in Bali.) The remains of Zhishanyan Culture found by the Japanese excavation was the very first prehistoric site to be discovered in Taiwan, and the artefacts left behind by culture represented a group of people who lived during the late Neolithic period. In fact there are multiple prehistoric cultures who have left traces here, but the Zhishanyan culture is special in that it was dug up from below a later water level, so the preservation of many items was far better than could be seen for the other groups. Archaeologists have found stone, bone, pottery, wood, ropes and the remains of different foods. From these remains it is possible to determine that the people of the Zhishanyan culture were farmers, fishers and hunters.

Further on still, right near where I started the walk, there are signs of more recent burials – many tombs are set into the hillside here. My companions shuddered when reading the information boards, due to the scarcity of suitable burial land and the lack of record keeping in days gone by, the bodies are often buried somewhat haphazardly on top of each other – sometimes newer graves disturbed previously interred individuals. There are no new graves here, but even the old ones were enough to send one of my Taiwanese friends hurrying along the path to somewhere brighter. Given the events that Zhishanyan has borne witness to, I’d say it’s probably not a very good place to visit if you are especially superstitious.

How to get to Zhishanyan

Google Maps address: the steps that I started at are next to a playground and opposite a seafood shop on Zhicheng Road. You can also head up via the 120 steps.

GPS location: N25 06.145 E121 31.805

Public transport: you can walk or take a YouBike from Zhishanyan Station, it is about 1km away. There is one YouBike stand outside exit 2 of the station and another next to the hospital to the north of the hill.

Zhishanyan Trail Map

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)

Come and say hi on social media:

This is the bit where I come to you cap in hand. If you’ve got all the way down this page, then I can only assume that you’re actually interested in the stuff I write about. If this is the case and you feel inclined to chip in a few dollars for transport and time then I would appreciate it immensely. You can find me on either Ko-fi or Buy Me a Coffee.