An Easy Wander Through a Rural Hakka Town

My plan for the day was to walk Shiguang Old Trail just a few stops away from Xinpu, but I ended up finishing that around midday, and with some much time left, it seemed silly to waste the journey by not exploring a little further. So I got on a bus from Shiguang and asked the driver if it stopped in Xinpu. He said it did, and—in a demonstration of the sweet thoughtfulness Taiwanese are famed for—when it got to my stop, he got up and turned around to make sure I was disembarking. And disembark I did, right next to Xinpu Guanghu Temple (新埔廣和宮), more on that later.

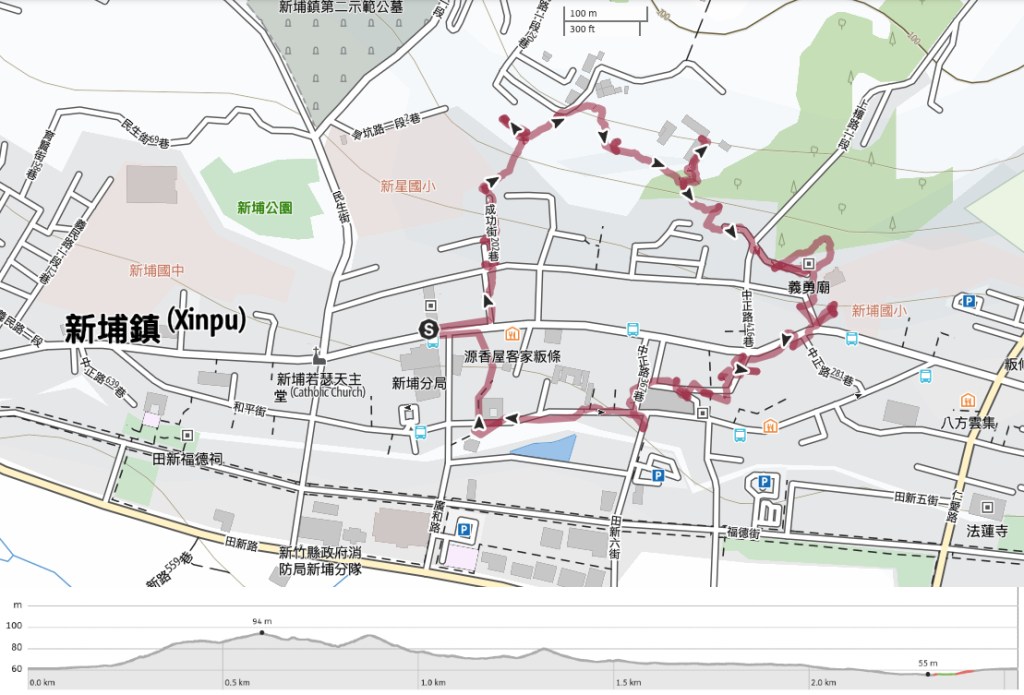

Distance: About 2.5km.

Time: The walk might only take an hour, but I advise allocating a couple of hours or half a day to explore the area.

Difficulty: This is a very easy stroll around a small town. The biggest challenges are the uneven pavements.

Total ascent: Under 50 metres.

Water: There are cafés and stores along the way, so you don’t need to carry anything if you don’t want to. But if you take a water bottle, you can fill up in a couple of the temples.

Shade: Not enough shade for people with sun-sensitive skin.

Mobile network: Perfectly clear throughout.

Enjoyment: I enjoyed exploring a little town that I previously had known nothing about. There are loads of old buildings if that’s your thing, and I personally found the temple art to be a wonderful unexpected treat.

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map and GPX file.

My plan was to do a loop of the town, taking in the hillside park, a couple of old houses, the old street and a washing pool. So with my back to the temple, I headed left up Zhongzheng Road.

Blocks of tofu drying on racks outside a shop.

When I hit Zhongshan Road, Lane 580, I took a left turn and headed towards a temple.

On the wall were the ghosts of noticeboards bearing posters: a missing dog called Laifu, sausages for sale, rooms for rent, a religious recruitment post, the kind of stuff you’ll probably see in small towns all over the place.

The lane crosses over Chenggong Street and heads towards Wenchang Shrine. I didn’t go in, but I enjoyed the echoes of an older building on the wall in the car park.

My path took me up the steps beside Wenchang Shine. Google Maps and some characters on the steps label this as being “好漢坡” or “Heroes Slope”. I’ve encountered many other climbs with the same moniker, and I can quite safely say that this one is by far the least taxing of the bunch. I guess it is the biggest hill in the neighbourhood though.

A map of Xinpu attached to the wall beside the steps.

At the first junction, I decided to keep heading up the steps on the left, then at the second, I took the flatter road on the right. But not before taking a quick detour up the steps to visit a temple.

Beside a large banyan tree stood a small shrine with a be-hooded Tudi Gong and his white-haired wife.

Back on the road, I decided to follow, I passed an old building before taking a turn off on the right down a path headed to Japan Park (日本公園). You might wonder, what with Taiwan and Japan’s history, whether that bore any relation to the park’s name, but no. It’s due to the many varieties of cherry trees that have been planted here.

The path arrives at an open area with a few benches and decorations including Orange Brother here.

The path cuts along the front edge of the clearing offering a clear view of the town stretching out below.

I stuck to the steps as they curved downwards, then at the very bottom took a left turn. (Actually, I took a detour up to the left to look at an old house, but it was thoroughly underwhelming.)

Close to the bottom, there was a small and perfectly formed nest that had obviously fallen out of a tree.

At the end of the steps, I kept to the left, heading towards Fude Temple.

As with a couple of the other temples around here, this one has steps painted with patterns only visible from the bottom. In this case, a dog and a squirrel make odd companions against a backdrop of green mountains and the faded remains of an earlier design.

After walking down the steps, the only way to go is left. I soon reached Shangzhangshu Road, crossed straight over and headed to the right of the steps towards another temple. (The steps head up towards an old banyan tree, but after taking a look, I’m not sure I can say it’s worth your effort.)

The next temple however, that really is worth the effort.

Inside Yiyong Temple (義勇廟), I noticed that the women in the artwork on the walls were unique both in that their faces all seemed to be based on the same woman, and because their bosoms were noticeably more voluptuous than those of women in similar religious murals.

Curiosity piqued, I wandered a little further in and spotted this pair of beauties. Each painted in the space above the two side altars.

Then, turning my eye to the smaller, usually more inconsequential panels reserved for depictions of birds and bountiful fruits, I spotted these decidedly very unusual images. The characters themselves aren’t unusual, the clam goddess and mermaid appear in many places where this type of religious imagery/folklore is recreated, but this was my very first time seeing bikinis painted into the murals in a temple. I was curious and had made up my mind to try and find out who the artist was on my train journey home. (There’s more to come on this subject later in.)

Continuing my wander, I took the steps (turn back, you’ll spot a rooster on them), and spotted an old photo of the earlier temple.

Opposite the photos, a renovated Japanese-style wooden building, which was once the residence of Xinpu Elementary School’s principal, now serves as a small information center/museum to introduce Xinpu and the Hakka folk who settled here. (Unfortunately, it was closed on the day of my visit, so I remain ignorant.)

I turned right back onto Zhongzheng Road, (the main road through the town), then crossed over and headed down the brick-paved Lane 311 in search of the old market.

A slightly bizarre mural adorns one of the walls along the lane. A cheerful modern-day rice-picker brandishes a bushel of rice while a vaguely perturbed, tufty-eared squirrel appears to be imprisoned in some type of storage space behind her.

My visit to the town was in the afternoon, so all but a handful of the stores in the old street and covered market were closed for the day. All of the produce vendors had long since shut up shop and tidied their wares, and the only stores open were a couple selling either household goods or products targeting tourists. It seems like quite a large market for such a small town, but it must also serve smaller local communities in the surrounding area.

Winding my way through the markets and backstreets, I headed for the next street over.

Turning right onto Heping Street, I soon found myself in front of the first of a couple of historic buildings. This is the Zhu family’s ancestral hall (朱氏家廟). It’s separated from the street by a wall and seems to have been renovated in the not-too-distant past. On the far side of the street from the shrine of past Zhus, a short flight of steps leads down towards one of my main reasons for stopping off at Xinpu: Pangxie Xue Washing Place (螃蟹穴洗衫窟).

Ever since I saw my first clothes washing pool whilst walking the Tamsui-Kavalan Trails, I’ve developed a bit of a fascination for these living relics. In this case, it seems the pool has been preserved for the purposes of memorialising an older way of life, but across Taiwan, there are still many of these which are in regular, daily use. Why am I drawn to them? I can’t really tell you. But I find myself wanting to visit and document them.

This back street is rich with traditional Hakka architecture (although sadly, none of the buildings were open to the public when I visited). Set back from the road behind a grassy lawn is the Pan Family House (潘屋). The Pan clan built their house in 1815, and undertook widespread improvements in the 1860s.

Nearby, another grand structure is the Liu Clan Ancestral Hall (劉氏家廟). Built around the same time that the Pan House was undergoing upgrades, Lius from all over the surrounding area contributed to its construction and upkeep. The presence of a shared ancestral hall for all people in surnamed Liu would have been one way to strengthen the bonds between immigrant families as they grappled with the challenges of life in a new land.

A sleepy cat giving a good summation of Xinpu’s general vibe and character.

From Heping Street, I turned up a narrow lane beside the Liu Family Ancestral Shrine.

Many of the humble buildings tucked into the backstreets are not as carefully preserved as the grand shrines and family halls. The lane soon re-emerges onto

The lane re-emerges onto Zhongzheng Road, and from here I turned left.

The next (and final) stop of the day was Xinpu Guanghe Temple (新埔廣和宮). Although it looks quite small from the narrow frontage, it actually stretches back for a long way.

I loved the pair of pig statues flanking the temple’s main door. They are modern (and more ethical) iterations of the inhumane Holy Pigs. Hakka communities have a cultural practise which involves community groups competing to fatten up pigs to hideously large proportions before slaughtering them and parading them around the town. These days, the custom still persists in some corners, but elsewhere, communities have found ways of continuing it without the cruelty.

Inside, I spotted some familiar-looking faces—the same artist who had painted Yiyong Temple had obviously had a hand in decorating Guanghe Temple too. Bikini-clad bathing beauties frolicked in the waves…

…and odd gremlins reached up to pinch at their tails.

Just as with the paintings in Yiyong Temple, many of the women appeared to have taken the same model as their muse by an artist who seemed to have a particular fascination with bosoms and feet. I found these depictions curious enough to warrant sharing online, and someone on Twitter swiftly identified Liao Fu-Chin (廖鳳琴) as the artist. Liao has earned a reputation as being a rather “provocative” temple artist. In his own words: “Young people are usually OK with them, but rural grandmas not so much.” Over his career, his depictions of female figures from legends have become increasingly risque and have been accused of starting fights between Tudi Gong (the god of the local land) and his wife.

Although I hadn’t heard of him before stumbling across his art, Liao is in fact, an infamous personality in the world of temple decorations. He has been interviewed numerous times by journalists who seem to struggle to get a sense of whether he is just an artistic soul with a very specific taste or a pervy fetishist trying to corrupt society’s values. The articles mention—sounding faux-scandalised—the fact that he spends his nights beside homemade sex dolls (converted store mannequins), as well as the fact that he sees his art as being no different to all the revered European art that is simultaneously revealing and religious.

Whatever your personal opinion on Liao and his art, I was glad to have learnt of his existance.

How to get to Xinpu

Google Maps address:

Public transport: From the bus stop outside Hsinchu TRA Station you can catch the 5619 via Xinpu or the 5620 via Guanxi and alight at any of the several stops in Xinpu. (I think the 5619 also runs past Zhubei TRA Station if you’re coming from the other side.)

Further reading: For some more information on the historic structures in the town, you can check out this blog post and if you’re interested in reading more about the artist responsible for all the busty temple beauties, you can read this old PDF of a Taipei Times bilingual feature. There’s also a YouTube interview with him (Chinese/Taiwanese only).

Nearby trails:

- Raknus Selu Trail Day 2

- Raknus Selu Trail Day 3

- Raknus Selu Trail Day 3 via BAILING PAVILION

- Raknus Selu Trail B Route – Lianhua Temple to Guanxi

- Shiguang Historic Trail

Xinpu Walk Map

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)

The shrines are looking the best ever

LikeLiked by 1 person

These are some very special shrines!

LikeLike