Deep in the mountains of Hsinchu, there are several groves of giant trees. The ones at Smangus and Beidelaman are both well-known and much-loved walks, but I’d heard comparatively little about those covered here. The walk and the trees take their name from nearby Cinsbu Tribal Village. If you’re wondering why Cinsbu doesn’t look much like a standard romanisation of Chinese characters, that would be an astute observation—it’s not. Zhenxibao is how the Mandarin characters are rendered in English, and Cinbsu is the self-given Tayal (or Atayal) name. Going by my experience in Smangus, where the word “Koraw” encapsulates information about the fertility of the soil in an area and the way it stains a farmer’s clothes after a day’s work tilling the fields, Tayal names seem to have a knack for conveying very specific concepts in a single word. Cinsbu is further proof of this, as signs at the trailhead state that this short word means, “The sun is already shining on the land here while you’re still deep in sleep in early morning and will continue to shine until evening comes. The day is warm and the night is cold in this land where disease and pests are extinct and crops grow well.” It is an impressively dense toponym.

Names aside, this walk (voted one of the 100 best hikes in Taiwan), is a rewarding foray into Taiwan’s mountainous forests.

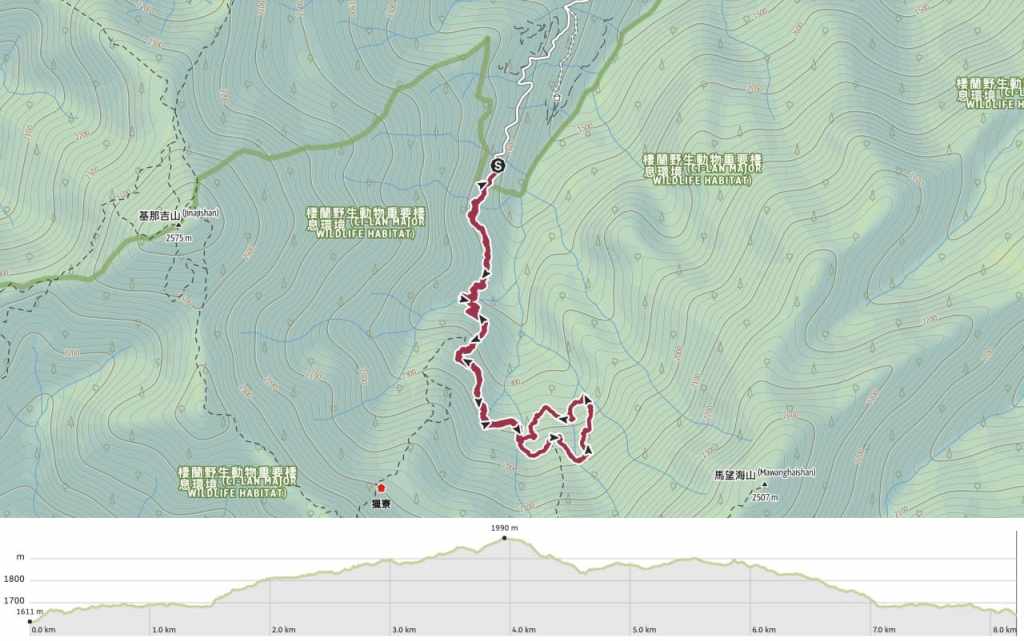

DISTANCE: About 8.2 kilometres.

TIME: 4-6 hours depending on weather conditions and how fast your group is.

TOTAL ASCENT: A little under 400 metres.

DIFFICULTY (REGULAR TAIWAN HIKERS): 4/10 – For anyone familiar with Taiwan’s trails, this walk is an easy-moderate hike. Technically speaking, it’s pretty easy, but the distance, elevation gain and steepness will make it tiring.

DIFFICULTY (NEW HIKERS): 6-7/10 – For anyone new to hiking in Taiwan, this would likely prove moderately challenging. The walk itself is not dangerous, but the elevation gain and steepness would prove tiring. Additionally, arranging transport could prove challenging.

SIGNAGE: Signage is minimal but the route is very simple. There are only two junctions, so there’s bery little chance of going the wrong way.

FOOD AND WATER: I took and drank about a litre of water and had a few snacks with me too. You’d be better off bringing supplies with you because places to stock up on the way here are few and far between.

SHADE: This walk is well-shaded the whole way.

MOBILE NETWORK: A little bit patchy.

ENJOYMENT: This is a beautiful walk among giant trees and it’s well worth the effort if you can get there.

SOLO HIKE-ABILITY: The only thing that would make me think twice about walking this route alone is the fact that it’s so far away from everyone and everything.

OTHER: Given how deep in the mountains this is, I would definitely advise making a weekend of it. There are a few B&Bs in Lower Cinsbu Tribal Village

ROUTE TYPE: There and back with a small loop at one end.

PERMIT: None needed.

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map and GPX file.

DIRECTIONS:

The drive to the trailhead Cinsbu trailhead carpark is a rather bumpy and not all too pleasant. We broke it up with a short pause at the pretty stone structure of Cinsbu Presbyterian Church, but even so, I was very happy to stretch my legs. From where we parked, a track slopes up to meet the start of the trail proper.

A prettily dappled path winds through the forest. Enjoy this comparatively flat part while you can, because it soon kicks things up a gear.

The understorey is cloaked mostly with ferns, but there were also a lot of these Taiwan cobra lilies (so named because, beneath their glossy leaves, they have a single hooded flower that somewhat resembles a cobra in a defensive posture).

After a couple of hundred metres, the trail begins to dip down.

We descended steeply to a rocky creek bed. It’s not immediately obvious, but trail cuts straight over and up the far side here. It would appear that the trail has shifted a couple of times over the years, likely due to damage caused by heavy rains. In fact, hikers have previously needed to be rescued from this particular trail after heavy rains caused one of the streams to suddenly swell.

On the far side of the creek, a raised wooden walkway leads onwards and upwards.

Before long, the steps give way to a dirt trail once more, although the ascent persists.

We passed quickly through the first rest and seating area and soon found ourselves at the second. Impressively, there’s a toilet block up here and even more impressively, it wasn’t vile.

After taking a few minutes to catch our breath, we pressed onwards. Just up from the seating area, there’s a fork in the trail. We took the left and easier heading towards Cinsbu A Grove. The one on the right heads to Cinsbu A Grove and Dulong Pool (毒龍潭, also sometimes translated as Poison Dragon Pond).

A second creek bed—this one almost dry after a few weeks with little rain.

The path climbs to a second fork. This is the start of a meandering loop through the Cinsbu Giant Tree A Grove. You can head either way, but going right for a counter-clockwise is marginally easier.

A multi-leafed Paris. Along with all the cobra lilies, this was the most common flower seen along the way. They’re not showy, but there’s something about them that I find exceptionally elegant.

Very soon, we found ourselves walking in the shade of giants, but as ever, photos feel absolutely incapable of capturing the full scale.

Many of the grander specimens are surrounded by a fence to protect their roots from trampling ramblers.

Many of the giant trees have been give Tayal names bearing reference to tribal myths and legends. One of the first few we came across was called Wal-m’yungay (人變猴子). In English, the trees name “Person who Became a Monkey” and it represents the story of how monkeys came into existence. According to the Tayal tale, there was a boy who was especially skilled at breaking hoes. Every time he went to the field, the handle of the hoe he was using would snap. One day, tired of having to fashion new tools, the frustrated boy stuck the handle into his butt. Almost instantly, the handle became a tail, sparking a complete transformation from boy to beast. The boy’s brother who had been working nearby hadn’t seen what had happened, so he was shocked to see a monkey in the field. The monkey-boy screeched desperately at his brother, trying to say “It’s me! It’s me!” But all that came out of his mouth were monkey sounds. From that day on, farmers have had to contend with monkeys trying to steal their crops.

Ferns growing on the branches of Wal-m’yungay.

I think this is the only spot on the whole trail that offers a view out of the forest.

As with most giant trees, these ones are clustered around water sources. Streams cross cross the grove and there are several points where we needed to cross the water.

In a couple of places, simple wooden bridges have been constructed, but in others, we found out ourselves picking a careful route over the rocks.

Ipuy (以布依). I’m not sure where this name comes from.

Temu Pyray (鐵木 比賴). Another mystery name. This is one of the few named trees that you can get close enough to touch.

Even where there aren’t any giant trees to admire, the trail is pleasant and pretty.

The largest of the trees in this grove is Sehu Buta (賽互 波塔), formerly known as “the King” (國王). It is, without doubt, a spectacular tree and we paused to admire it as we finished off our snacks.

From there, we continued following the path over another stream, where I got my feet a little wetter than intended.

A deceased giant has fallen beside the trail, its hulking corpse spanning a small valley.

The trail curves around to meet the spot where its roots were ripped from the soil and you can almost see inside the trunk.

As we were nearing the end of the loop section, we encountered this mountain keelback (史丹吉氏斜鱗蛇). The silly creature seemed intent on racing us along the path and didn’t appear to realise that could have slithered off in any direction. After keeping up with us for several metres, it found a hole in a rock and darted in.

Two of the last giant trees we passed had signs that declared them to be Halus (哈路斯) and Wal-m’kuali (人變鷹). Formerly, they were called Adam (亞當) and Eve (夏娃) on account of the fact that one had a protuberance and one had a cavity that put people in mind of certain anatomical features, but like Sehu • Buta, they were rechristened at some point over the past decade to bear names that represent characters from Tayal folklore.

Halus was a giant that lived among the Tayal. Not just unusually large in stature, Halus had also been blessed with an exceptional penis. In fact, it was so long and so sturdy that it could be used by tribespeople as a bridge to help them cross rivers and valleys. Halus was happy to be of assistance to his people in this way, but unfortunately, he didn’t learn to keep his *ahem* gifts to himself, and would often harass village women. To punish him, the tribespeople tricked Halus, saying that if he went to the bottom of a mountain and lay down with his mouth open, delicious food would fill his belly. Halus, anticipating a free meal, did as he was instructed, but there was no food. Instead, the villagers rolled burning hot rocks down the slope and into Halus’s mouth, causing him to die where he lay. In death, the giant’s body became a mountain and his blood turned into rivers, and although the story doesn’t say what became of his massive member, but at least it’s memorialised here.

The story of the Wal-m’kuali tree (the Chinese name translates to “Person Who Became an Eagle, and I think the Tayal name means something similar) also deals with bad behaviour and retribution, albeit in a different way. In this tale, there was a lazy and unkind mother who always used to get her daughter to do the chores around the house. Being well behaved, the daughter did as she was told, but she would always look forward to the moment her father returned to the village after a hunt and she liked to dress up to greet him. One day, knowing that her father would be on his way, she asked her mother to give her a necklace so that she could look pretty. The mother said “Sure, sure, but first make sure we’re all stocked up on water and firewood, and make sure the pigs are fed.” The girl did this, then returned to ask her mother once again for the necklace. This time, the woman said, “OK, but first go out to the fields and dig up some sweet potatoes for dinner.” The girl, long used to her mother’s demands and false promises, trudged back outside. Almost as soon as she had left the house, there was a great commotion outside, a big flapping of wings. Alarmed, the mother rushed to see what had happened and found her now be-winged daughter perched in a tree. Too late, she attempted to coax the girl down by offering her the necklace, but the change couldn’t be done and the girl-bird flew away.

Some more exquisite leaf details seen along the trail. The one on the left had obviously been used as a nursery for a bug of some kind.

Heading back the same way, we ended up quite spread out, each enjoying the quiet of the forest along

GETTING TO THE CINSBU GIANT TREES

Google Maps address: The walk starts from the end of a dirt track deep in the mountains of Jianshi District. There’s a carpark here with plenty of space for cars and scooters. However, the road leading up here is both narrow and bumpy, so if you’re driving, make sure you’re up to the challenge of getting there.

GPS location: N24 33.210 E121 17.570

Public transport: There is no public transport to the trailhead. If you don’t have your own wheels, you’ll have to either rent them or join a group. Luckily, this seems to be quite a popular trip among groups. Alternatively, if you stay in a B&B at Lower Cinsbu Tribal Village (which can be accessed from Neiwan on the twice-daily 107 bus), you could ask your hosts if they’d be able to do a drop-off and pick-up service. The B&Bs are used to serving hikers, so they likely already provide this service.

Further reading: Richard Saunders—the original Brit writing about Taiwan’s trails—has written about this trail and the walk to Poison Dragon Pond here. For Chinese information, you can check this site.

CINSBU GIANT TREE TRAIL MAP

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)