RSA26 – RSA29.2

Day 6 on the Raknus Selu was a special one. Leaving Beipu behind, the trail climbs towards the border with Miaoli, passing numerous temples along the way. For me, the highlight of this day was watching the sunset from the courtyard in front of Quanhua Temple.

RAKNUS SELU STAMPS: There are two passport stamps to be found along the trail today.

- RSA27: Located at Nanwai Community Activity Centre (南外社區活動中心)

- RSA29: Located at Lion Mountain Visitor Centre (獅山旅客中心)

DISTANCE: 12.9km (I actually walked about 14.4km because of my lunchtime detour.)

TIME: It took me 6 hours including a very long break for lunch.

TOTAL ASCENT: About 530 metres. Most of this is covered on roads though, so it’s not too taxing.

DIFFICULTY (REGULAR TAIWAN HIKERS): 3/10 – This is another easy day. There’s some climbing to do, quite a lot of junctions to navigate, and a fair amount of distance to cover.

DIFFICULTY (NEW HIKERS): 4/10 – Navigating and the length of the day’s walk are probably the two biggest challenges, but this should still be easy even if you’re unfamiliar with Taiwan.

FOOD, DRINKS & PIT STOPS: I took a 0.5L refillable bottle which I filled up at Jihua Temple and Lion Mountain Visitor Centre. I also stopped for coffee and lunch part-way along the way. If you’re also planning to stay at Quanhua Temple, dinner is served promptly at 5:30pm.

TRAIL SURFACES: Mostly roads, some unpaved trails.

SHADE: Lots of this is completely unshaded. I needed a hat and long sleeves even in winter.

MOBILE NETWORK: There was a short stretch in the middle where I lost mobile service, but otherwise it was clearer.

SOLO HIKE-ABILITY: This should be perfectly ok for solo hikers. The biggest risk factor is running into dogs, so as long as you’re confident about that, you’ll be fine.

SECTIONS COVERED:

- RSA26: Beipu → Hsinchu District Road 37 → Jihua Temple → Shiyingzi Bridge (竹37→濟化宮→石硬子橋)

- RSA27: Shi’en Historic Trail (石峎古道)

- RSA28: Shi’en Historic Trail Trailhead → Lion Mountain Visitor Centre → Lion Mountain Historic Trail Trailhead (石峎古道口→獅山旅客服務中心→獅山古道口)

- RSA 29.1: Lion Mountain Historic Trail → Bogong Temple (獅山古道→伯公廟)

- RSA 29.2: Bogong Temple → Lion’s Head Mountain Archway (伯公廟→獅頭山牌樓)

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map, GPX file and all the other practicalities and if you would like assistance booking your stay at Quanhua Temple, you can click here.

DETAILS & DIRECTIONS:

When I woke up, it was around 7 o’clock and the road outside was busy with all of the workers heading off for their sad Saturday make-up day. Outside, the air was all white with the early morning haze that you often get in these parts, although the sun was already out and working on breaking through. I made a coffee to drink whilst sorting my things, went down and bid farewell to my friendly host, and was on my way just shy of 8 o’clock.

My first port of call was breakfast. Initially, I’d planned on making my way towards the public market to see if the danbing vendor had any vegetarian-friendly offerings, but while I was on my way, I spotted this almond tea and youtiao shop. I’d wanted to try it the night before, but was overfull from my lei cha experience, so I’d had to pass up the opportunity. It was adequate, far as breakfasts go (maybe not quite worth the $70 price tag, but this is a tourist town so that par for the course), although I learnt the hard way that almond tea is served at temperatures hot enough to burn the sun.

When I emerged from the breakfast shop, the sun had all but burnt up the morning haze, and the sky was on the cusp of turning blue. The almond tea shop is just next to Citian Temple (慈天宮).

I’d visited the day before and hadn’t planned to return, but the light was catching the incense smoke so beautifully that I was drawn in.

8:27 – When I was ready to start walking in earnest, I returned to the point at which I’d left the RST the day before to pick up the trail. Head towards the fire station, then take a left turn onto Nanxing Street and follow it as it takes you out to the southern edge of the town.

The first view of the day came quickly. When I glanced to my left, Mount Egongji was rising over the lingering haze. That particular peak would accompany me for several hours to come.

The road narrows as it heads down, and at the bottom, I met a woman out taking photos of an artfully decaying brick wall. She tried to entice me to be her model, I’m not sure why, we hadn’t been chatting. I encouraged her to let me take her photo instead (on her phone, not mine!), and ended up taking a really pretty picture for her.

08:34 – At the junction, take a left and follow the road downhill towards a stream.

The scenery is green and rural. Small parcels of farmland growing fruits and vegetables are interspersed with messy grassland and the odd pool here and there.

08:37 – The road heads down to cross Dahu Stream, passing Shuangan Bridge (雙安橋) before starting to climb again. Built in the 1850s, local historians say that this glutinous rice and red brick bridge was built as part of a dowry exchanged between two Beipu families. It’s also noted that as well as being used by people, a channel running the length of the structure seems to indicate that it played a role in irrigating local farmland. Back in 2016, Shuangan Bridge was in a sorry state. The stone base supporting the pillar on the Beipu side of the bridge had all but crumbled away, and the whole structure was hidden amongst the weeds. Now it’s been tidied up a bit a new base has been built, and the brickwork arches are supported by a steel frame. Scaffolding on the bridge makes me wonder if the restoration work is ongoing, but regardless, it’s currently looking far better than it did a few years ago.

On the very outermost edges of the built-up area, I passed a patch of farmland that had been given over to growing this lilac-coloured flower crop. On the other side of the road there are graves, and on a sloping driveway, I met a pack of dozy dogs sunning themselves.

Before long, I’d passed the second derelict bridge of the day. This is Dalin Old Bridge, and if you walk down to look at it from below, you’ll see that much of the walkway has crumbled away.

08:52 – Then soon after that, a wooden pavilion shelters a clothes-washing pool. Photos on Google show it in use relatively recently, but it looks like it hasn’t had water in it for a while.

09:02 – At the next junction, the RST keeps following Hsinchu District Road 37 as it bends left, but my attention was caught by the place name, Fanpokeng (番婆坑) on one of the green finger posts. Broken down into its component parts, the name is a racial slur used to describe aboriginals, maybe something like “savage”, then the second character means “wife”, and the third is “pit”. The combination made me wonder if the area had a history of inter-marriage between Aboriginal, Han an Hakka communities and, sure enough, when I got home, I found this:

「番婆坑」為北埔、峨眉交界處的礦區,由 於早年在客家先民入墾後,當地的原住民女 性移居至此,因此得名。

According to the above quote, back when Hakka folk first moved into the area, local aboriginal women immigrated into the village and married into the Hakka communities. But since this is the promotional blurb from a Hakka restaurant’s website, I thought it was worth digging a little deeper.

For my efforts, I was rewarded with this second, less rosy tale. This tale comes courtesy of a local shop owner as told via another person online, and as such, I cannot vouch for its accuracy. However, it’s certainly true that relations between the different ethnic groups inhabiting this area have not always been smooth. In this alternative telling, the land around modern-day Beipu was originally inhabited by members of the Saisiyat Tribe. Then during the Qing era, a huge influx of Han and Hakka settlers arrived, and (under the land reclamation regulations of the time) were able to stake their claim on the land. Naturally, the displaced Saisiyat were aggrieved, and the settler’s incursion onto tribal lands made them a fair target for being headhunted. Now, with grievances on both sides, the mistrust and hatred intensified, and one day, when the Saisiyat men were away from the village, Han settlers went in and slaughtered the tribe’s women. In a belated retrospective moment of remorse, the Han settlers decided to name the place in remembrance of the murdered women. Later, Hakka, Han and Aboriginal groups living in and around Beipu would put aside their differences and band together with the Japanese as a common enemy. I am curious about what people feel when they see this name now. As a foreigner, I can see the name and understand from a purely character-by-character, linguistic perspective what the name means. I can know objectively that this is “not a good name”. But I feel nothing. When I showed the sign to my partner, (who counts herself as Han Taiwanese going back many generations with a dash of Hakka somewhere in there), I detected a note of discomfort around the word in her reply. Is this how most people feel? And what about those of aboriginal descent? Do people ever talk about changing place names like this in the same way that the US and the UK are grappling with whether or not to remove the statues and street names that remind us of the not-so-golden moments from history?

The road climbs steadily towards the hilltop village of Jiufenzi. Along the way, I enjoyed the kind of sights that come with rural life; single-storey brick buildings, views over the valley, and small wayside shrines. This one is a small alcove carved into the rock face beside the road with a stone marker reading “覡婆姐” or “Xipo Jie”. Interestingly, it’s another place tied to women (or rather a woman), of the past. Two nearby towns lay claim to be the hometown of the woman commemorated here. Hengshan bases its stake on the fact that they have a shrine dedicated to Xipo Niangniang, and other local historians say that the woman was the unmarried daughter of a family from Shibitan. The latter was known for travelling around dishing out medicine, delivering babies, performing spiritual cleansing, and match-making. The woman is said to have died in an accident when crossing the river at Shitan and her burial was paid for by those who had been healed by her knowledge of medicine. Whoever she was, locals have continued to pray to her after her death, claiming that her medical advice is still remarkably effective.

The current stone marker at this shrine is relatively new. The old one was stolen back in the 1970s, when Taiwan was in midst of a mark six lottery craze and everyone was seeking their own deity to advise them on the numbers.

Several of the old folk residing in Jiufenzi were sat outside their houses, some positioned to enjoy the view, others just watching the world pass by. I overshot my turning originally and consequently ended up meeting and playing with this rather adorable pup for a while as I chatted to her dad.

9:22 – The RSA takes a left down this single-lane road. I spotted a sign pointing towards Have a Picnic, the pizza shop at the start of Five Finger Mountain Trail, and was impressed by the effort the owner must have gone to in order to advertise their place (from here, it’s almost another 10km of winding mountain roads).

The road winds down towards Nanwai Community. The first building on the right as you head downhill is a tiny one-room hair salon which looks like it’s remained unchanged for decades.

9:37 – I arrived at the community centre to find it very shut, despite Google showing that it should be open. Since I’d already made it this far, I decided to call the number and see if there was anyone around. When I got through, an older man answered the phone and said he’d be over in a minute or two. When he arrived, he explained that the centre is usually closed, but that he lives just up the road, so people if anyone ever stops by, it’s easy enough for him to come and let them in. I asked if he knew who the guy on the stamp was and he shrugged, saying that all he knew was that it was a Taiwanese person who walked this road sometime in the past. In fact, the information given about this dapper chap does not make it clear whether he is Lai He (賴和), aka The Godfather of Taiwanese Literature, or Tu Tsung-ming (杜聰明), who is famed for being the first Doctor of Medical Sciences in Taiwan. Both men are said to have travelled along the paths that make up the Raknus Selu Trail. However, since photos of both exist, my money is on it being Lai (on account of the moustache).

Lai was a Changhua native, born to a Hakka family and educated in the Japanese school system of his era. As he grew up, Lai began to write, first in Chinese, and later in Taiwanese, something which made him a bit of a headache for the authorities who were intent on getting their subjects to become good Japanese citizens. He also engaged in efforts to raise Taiwanese identity by helping to found the Taiwan Cultural Association. For his efforts, he was jailed twice, and during his second spell inside, he contracted an illness that would lead to his death. If you’re interested in seeing some, you can visit Baguashan in his hometown—here there is a beautiful metalwork panel with some of his works.

Side note: To the left of the passbook in my hand, you can see a photo of people holding flaming torches. I think this must be a photo of the annual Beipu Lantern Festival. As is fitting for such a rural community, the lantern festival here involves townsfolk carrying torches fashioned from bamboo, oil, and a rolled-up wad of spirit money. (The people who produced this video made their own torches before setting them alight.)

Passport stamped, I headed back on my way again. Foolishly, I forgot to take a photo of the next junction, but from Nanwai Community Centre, you need to retrace your steps about 50m, then turn left uphill following the fingerpost directing you to Jihua Temple (濟化宮). Soon, the road runs up to rejoin Hsinchu District Road 37. Turn left onto it and walk towards the unmissable huge red columbarium belonging to Jihua Temple.

10:10 – This is a good place for a good mid-morning break. There’s a toilet block beside the road, a small convenience store selling snacks and drinks, and the temple itself has water dispensers. I climbed the steps to take a look inside and top up my water. The layout of this temple complex is a little confusing. There are at least three levels, each of which seems to have its own administrative facilities. Either way, I enjoyed a brief rest here and left with a refilled water bottle.

10:27 – Heading onwards and upwards, the road comes to a junction. By now, I was familiar with the light but well-placed RST signage, so when I saw tags hanging on the left side of the road, it made me look up. Sure enough, the RST dives off to the right here, then mere metres later it takes the left lane and follows signs towards Dadi Farm (大地農場).

This was the first part of the walk which started to feel properly away from things. The road has no markings, and only one car passed me along this section. I could see several crested serpent eagles circling overhead, emitting frequent piercing shrieks, and for a while, the road follows alongside a gentle stream.

10:41 – When you reach Shiyingzi Bridge, head around the gate to take the track on the right. This is the start of Shi’en Historic Trail (石峎古道). The first part of the trail follows a track through shady woodland and past somewhere that looks like it’s in the process of being turned into a campsite/mountain karaoke spot.

10:50 – Look out for the turn off on the left that marks the start of the trail section of Shi’en Historic Trail. You’ll know you’re in the right place if you spot this scruffy lean-to storage hut.

It looks like a pile of random rubbish, but I think it’s probably a staging post for the gardener who has claimed a little patch of land further along the trail.

10:52 – I imagine the same farmer is responsible for maintaining this rickety bridge. When I say “maintaining”, what I actually mean is “throwing a new layer of bamboo poles and scrap planks down and hoping it sticks”. The bridge was several layers deep, with each layer showing increasing degrees of decay as they get further down the pile.

From the bridge, the path climbs a little, and then you see why there is so much crap and detritus all over the trail. Someone has carved out their own little patch of farmland here amongst the trees. It’s currently watched over by an army of politicians. Election banners like these are often recycled by the thrifty old folk who farm and build mountain shelters.

Between the farm and the stream, I spotted plenty of signs that the Thousand Mile Trail Association has been hard at work. Stones and wood have been used to shore up the trail, and in places, to make steps. It’s all very low-key and lightly done. This are is also obviously frequented by many wild animals because there are animal tracks criss-crossing the path (and because I startled a couple of barking deer).

The path dips to join a stream. I paused here to watch a grass lizard and eat the jujube that I’d been given the day before. On the far side of the water, you’ll find the only (very short) rope section along this portion of the trail.

11:23 – All too soon, the trail became a narrow track, then quickly a wider track. And then before you know it, a dilapidated farmhouse marks the spot at which you rejoin the road.

11:28 – The road winds it’s way towards a small community with a couple of older buildings scattered amongst what looks like newer holiday homes. Turn left past this collection of buildings.

The text above the doorway indicates that this is Qinghe Hall (清河堂).

The lane leading away from Qinghe Hall is lined with betel nut trees.

11:35 – Follow the lane until it crosses a river and joins Hsinchu District Road 41. Turn left onto the road and head up towards Lion Mountain Visitor Centre.

11:49 – Later you will need to return to this point and take the narrow lane leading uphill on the right in the first photo. The visitor centre is up the steps to the right in the second photo. There are toilets and a water dispenser that you can use to top up, and the stamp is located inside the visitor centre itself. It’s worth popping in anyway, because the bilingual information boards contain quite a lot of information about the area.

The stamp for this section is especially cute. It shows two hikers scaling the flank of a mountain-ish lion which is gazing down upon the old archway (we would pass through this very arch the following day).

Since I’d arrived at the tail end of the lion so early, I decided it would be nice to go and get a coffee, so I headed off on a little detour to visit Tenping Villa Coffee Shop (藤坪山庄). If you’re in the area and have a spare hour, I highly recommend it. The shop is an open-feeling single-room affair with a balcony extending around two sides and a view over a sloping garden towards the river. The boss had his professional-looking camera mounted on a tripod to photograph the birds and wildlife that were visiting, and was pointing out some of the species to another pair of customers. While I was there, a noisy flick of blue magpies gathered in the trees, and judging by Google maps, there’s a mongoose which frequents the area too. I think I spent a good hour and a half here enjoying the atmosphere before heading back to the visitor centre to continue my journey.

13:41 – It was getting on for two o’clock by the time I arrived back at the lion’s tail to begin my climb along Lion Mountain Historic Trail.

The trail is actually more of a road, although I think only three scooters passed me the whole time I was walking along it. A dramatic overhang shelters the first temple of the trail (a small brick land god temple with a blue and red frontage).

Then just a few steps further along, a sloping drive leads up to Wanfo Temple (萬佛庵). This was my third time visiting this trail, and the very first time I’d seen this one open to the public. First built in 1927 (although later reconstructed), Wanfo Temple is built into a cave like many of the temples along the length of the Lion Mountain Trail. The thee-sided structure with the mountain rising behind gives Wanfo Temple a very calm, cloistered feeling, and I imagine the nuns waking up here must feel their hearts sing when they step out into the sunny courtyard.

As with many aspects of Taiwan, this temple has revived the cutification treatment, statues of acolytes performing everyday tasks like sweeping and fetching water line the path up the temple.

14:12 – Returning to the main trail, I continued my journey up the lion’s spine. By a cluster of buildings (one of which has some wonderful duck-pattern curtains), I passed the turn-off for a short trail leading to Lion’s Tail Mountain. Then at this pavilion, there’s another turnoff leading to Qixing Sacred Tree.

14:15 – At the fork in the road, the RST takes the left and continues climbing. (By this point, my legs were becoming quite tired.)

The road passes a couple more temples, neither of which were open to the public, so I contented myself with looking at the plentiful cherry blossoms along the way.

14:35 – Just as you see the road start to descend and you might feel a sense of relief, the RST takes another left and darts up this flight of stairs heading towards Yuanguang Temple (元光寺).

I think I’ve become a temple snob in my years in Taiwan because Yuanguang Temple, with its clean Buddhist colour palate and simple decoration doesn’t do very much for me. (Although I did refill my water bottle from the dispenser in the courtyard, so that’s at least something I liked about it).

Leaving the temple of Yuanguang Temple through its red, cream and gold archway, I spotted a much more appealing temple a little off track on my right. This one was a land god temple with a mini kitchen under s curved shelter and another altar set up for (I think) a camphor tree. There’s just something about this kind of set-up that makes me feel at home.

Head up to a small snack stall next to a pavilion. The RST goes straight over and starts to go downhill. If you’re into peak-bagging it’s worth going to visit Lion’s Head Mountain. It’s only a brief detour (on the dirt path just to the right of the steps), and Lion’s Head Mountain is one of Taiwan’s Xiao Bai Yue.

Right next to the snack shop and pavilion, look out for this stone marker. This notes the spot at which Hsinchu and Miaoli Counties merge, so for those who have walked this trail all the way from the start, this is third of four counties you’ll pass through.

Shallow steps head downhill. In this direction, they seem so shallow as to be irritating, but they make perfect sense if you’re going uphill. To the right of the path is the imposing sight of Lion’s Head Mountain Rock Face. Naturally, this being a scenic area popular for many decades, the rock has been scarred with graffiti (or spiritual art, if you prefer).

14:53 – At the junction towards the western edge of the rock face, the RST turns left down some steps. However, if you haven’t visited the area before and you have time, I’d suggest that you take the path heading straight over. It’s only a little longer, but it’ll take you past both Kaishan Temple and Sheli Temple.

15:02 – The trail zigzags down to Daode Gate (道德門), and I decided to turn right and pay a repeat visit to Sheli Cave Temple. I think it’s probably my favourite of all the temples in the Lion Mountain trail and temple complex.

The temple’s main deity is the Queen Mother of the West (西王金母). Alongside her are Dimu Niangniang (地母娘娘), who, well, I’ll leave the description to the expert:

Worship of Dimu is flourishing in Taiwan today thanks to an important andinfluential devotee and benefactor. Stan Shih (施振榮), the founder of the highlysuccessful Acer computer company became a devotee of Dimu Niangniang because ofhis mother. Shortly after the company was founded, a huge number of IC chips werelost. Shih’s mother and all the family prayed to Dimu Niangniang. Finally, the IC chipswere recovered. As a result, Shih and some of the company member became thedevotees of Dimu Niangniang.

—David Eastwood, from a paper titled Taiwanese Folk Religions Examined from a Christian Perspective, link here.

You’ll also find Jiutian Xuannu here (九天玄女, AKA the Dark Lady of the Ninth heaven) who rides a phoenix, is credited with being the originator of the Luopan (羅盤, a kind of feng shui compass which she is often shown holding), and is associated with ‘the Taoist arts of the bedchamber’.

The highlight of this temple is probably the cave behind the main altar. (You have to go through the chamber on the right to access it.) But on this occasion, there was a large group watching a pair of robe-wearing Taoist practitioners perform some type of ritual, so I didn’t take any photos.

From the courtyard in front of the temple you can get your first view of Quanhua Temple.

Returning back towards Daode gate, I passed in front of Quanhua Temple and down the steps leading to Futian Temple. This is THE spot where all the famous photos of this temple are taken.

The ornately detailed roof of Futian Temple sits against the backdrop of Jiali Shan and Mount Xian, and in the gathering dusk, it is just too beautiful for words to describe.

On this leg of the journey, we stayed at the accommodation at Quanhua Temple. The entrance to the hotel is right in front of Futian Temple, and the rooms are all downstairs. I arrived earlier than Teresa, so I checked in first by myself and I have to say, I really did not like the woman who checked me in. I felt she was trying to push me into paying for a larger room or one with a view (the cost is only a couple of hundred higher, so it’s not much, but I was annoyed because she tried several times). She was also a bit prickly about the fact I didn’t have a passport on me, asking in Chinese, “How come you don’t have it?” I replied saying that since I’ve live in Taiwan, I’m not really a tourist and who carries their passport at all times in the country where they live, she wasn’t happy with this, but didn’t refuse me service (which apparently happened during the pandemic even to foreigners who hadn’t left Taiwan in years-even the ones who did have their passports – Welcome to Taiwan). She then photographed my ID on her personal phone as well as recording my number in the check-in book. I’m fine with having my details written down like everyone else, or even photocopied and attached to my reservation, but it felt a bit weird that she’d just taken a photo on her phone. The final point of discomfort was she basically forced me to out Teresa and myself by repeatedly asking if I was sure I wanted to share a bed. I was only able to get her to stop by telling her that we usually share a bed. After which, she was a bit off with us.

Regardless, at NT$1000 for the two-person room, and in such a neat spot, the place is still very worth staying in. It’s just a shame about the attitude of the staff.

The bedroom we stayed in had a very cosy feel. This is probably due to the wooden paneling and low ceilings, not to mention the authentically retro avocado-green bathroom suite. (Hot water is only turned on between 5pm and 10pm to conserve energy.)

Dinner is served at 5:30 in the hall opposite the hotel’s check-in counter. (I suggest taking your own bowls and utensils as the temple only has disposable ones, unfortunately.) It’s simple vegetarian fare—rice, several vegetable dishes, some tofu and soup. After picking up our meals from the serving hatch, we carried them out to the tables in front of the temple and ate our meals as the sky grew dark around us. At six o’clock, the temple wardens began their evening ritual. Using a mallet on a long pole, they beat the drum that was hanging from the rafters in front of the tiger door, then the dragon door’s bell, and finally the drums again. It seemed like the person doing it was being coached because he had a woman who repeatedly told him he needed to continue for “X” amount of repetitions.

By the time we had finished, the temple lights were brighter than the sky and the colours had an almost magical glow to them.

Before we went downstairs to sleep, we took a final look over the landscape below. The columbarium stood out against the distant hills, and the lights of Nanzhuang were visible in the valley below. I think staying here should is a must for anyone walking this trail.

GETTING THERE

Public transport:

- Getting to Beipu – The cheapest way is to get on the 1820 or 1820A from Taipei Bus Station and ride it to Hsinchu Bus Station (or as close as you can get). Then transfer to the 5626 from Hsinchu Bus Station and ride it to Beipu. It’s also possible to ride the HSR to Hsinchu HSR Station, then take the 5700 Taiwan Tourist Shuttle (bound for Lion Mountain Visitor Centre), and ride the six stops to Beipu.

- Getting back from Lion Mountain Visitor Centre – The 5700 Taiwan Tourist Shuttle will take you from the visitor centre to Hsinchu HSR Station.

- Getting back from Quanhua Temple – Walk down the steps to County Highway 124. The 5805 and 5805A shuttle between the bus stop here and Zhunan TRA Station.

Accommodation:

Staying in Beipu – I stayed in Beipugo Guesthouse and would definitely recommend it. I paid $1200 for a three-person room with a bathroom that was private but which I actually had to leave the room to access (I could have chosen a room with a shower inside for $1500 per night). There’s a communal seating area on the ground floor and another on the upper floor where the rooms are. Guests are given towels, toiletries, a small kitchenette with cups and tea, and use of a spin drier.

- Name in Chinese: 北埔口民宿

- Address: 314新竹縣北埔鄉南興街168號北埔老街旁

- Contact: 035804121

- Cost: $1200-1500 (midweek)

Staying at Quanhua Temple – Quanhua Temple offers basic rooms starting at $1,300 a night for a double without a view. The rooms are comfortable but do not have anything except for a towel (no shampoo, no hairdryer). The temple provides dinner (5:30pm) and breakfast (6:30-7:30am) for a voluntary donation (or for free). You will need to show some form of ID to stay here. If you need help booking Quanhua Temple hotel, you can click here.

- Name in Chinese: 勸化堂香客大樓

- Address: No. 242號, 17鄰, 南庄鄉苗栗縣353

- Contact: 037822563

- Cost: $1,300 for a two-person room without a view (updated 2025)

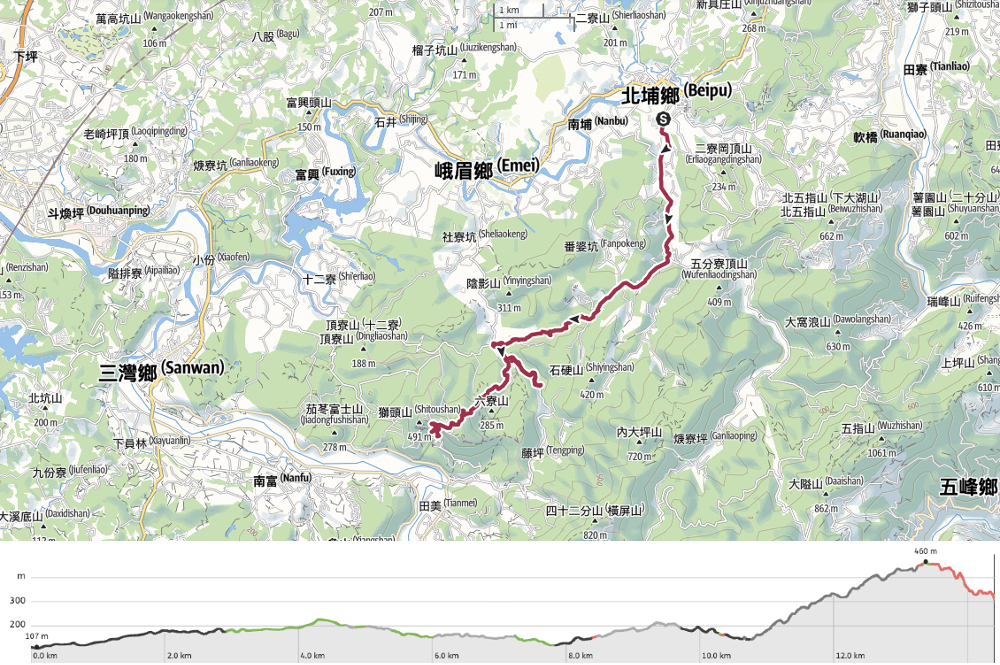

RAKNUS SELU DAY 6 TRAIL MAP

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)

If you enjoy what I write and would like to help me pay for the cost of running this site or train tickets to the next trailhead, then feel free to throw a few dollars my way. You can find me on PayPal, Buy Me a Coffee or Ko-fi, (and if you’re curious about the difference between the three you can check my about page).