MSTW SECTION 23

Day seven on the MSTW was a breeze compared to the challenges of day six. It follows County Highway 169 from the remote village of Lijia to the marginally less remote village of Dabang. Along the way, there are lots of tea fields and Dabang itself makes a perfect place to take a rest day to recover and enjoy the slower pace of life.

I had anticipated being far tireder and more sore by this point in my journey, so I booked to spend two nights here. As it happened, I was coping with the physical challenge of it better than anticipated and could have easily carried on the next morning. However, I’m glad I had this little break. Dabang and its near neighbour Tefuye are both interesting little places and an overnight stay meant I was able to explore them at a leisurely pace.

MSTW PASSPORT STAMPS: The’s one stamp along this section. It’s kept in the Tsou Cultural Exhibition Hall. Open Tuesdays to Sundays, 9am to 5pm. Closed on Mondays.

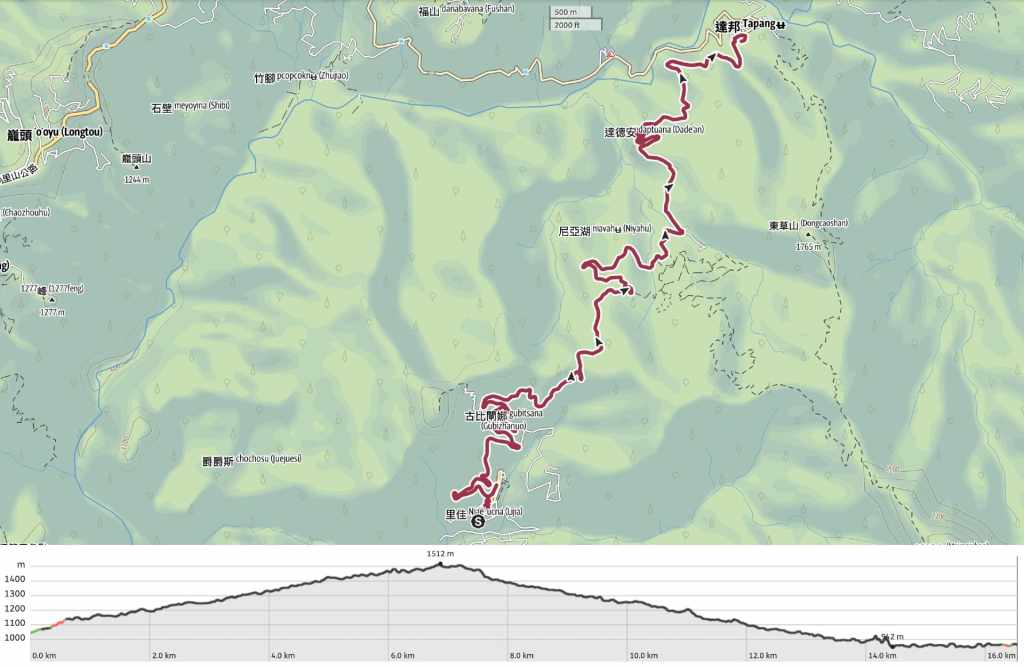

DISTANCE: 16.5 kilometres.

TIME: About five hours.

TOTAL ASCENT: A little over 600 metres with a similar amount of descent.

DIFFICULTY CONSIDERATIONS: This is a very straightforward day. It’s not long, not steep, and there isn’t a huge amount of elevation gain. Just watch out for farm dogs.

FOOD, DRINKS & PIT STOPS: There aren’t any places to pick up provisions in Lijia (that I’m aware of), but I could have easily taken an extra boiled egg and jam sandwich at breakfast if I’d needed. As it happened, I still had the last of my provisions from Dapu to keep me powered up until Dabang. Water is the same—after filling up and leaving Lijia with 1L in my bottles, there’s nowhere to top up until Dabang. Thankfully, that was plenty. Dabang has several restaurants and one old-school convenience store.

TRAIL SURFACES: Backroad the whole way.

SHADE: Shade is patchy along this stretch.

MOBILE NETWORK: There were some signal deadzones, but mostly OK.

SOLO HIKE-ABILITY: The only hazard on this stretch is farm dogs. If you’re confident in handling those, then you’ll be fine.

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map, GPX file and all the other practicalities.

DETAILS & DIRECTIONS:

The night before, my host had decided on my behalf that I didn’t need to wake up too early, so she instructed me to be ready for breakfast at 8 o’clock. I have a sneaking suspicion that 8 o’clock was aunty when wanted to serve breakfast because that’s when everyone arrived to eat. The spread included toast, congee, several vegetable dishes, and three types of locally grown and processed coffee. Since the aunty was occupied with making the coffees, the pouring of it fell to the guests, and I was quite touched when they made sure to bring the jug to my table too.

As the others filtered away to get ready for the day, the aunty persuaded me that I needed to eat more to solve what she percieved to be the dual problems of her having too much leftover food and me being too thin. She then instructed me to go on a little walk around the village so that my clothes could sit out in the sun to dry a little longer. So, I visited the nearby Romantic Cave Trail and enjoyed learning about Tsou culture and customs as I waited to be allowed to set off.

10:10 – By the time I was ready to head off up the road, it was the latest start I’d had on the whole trip.

Day seven started with a steep climb up one of Lijia’s two main streets. Looking back, the view is absolutely delightful. I can’t imagine how it must be to be a child growing up here in this village right at the end of the road. I asked the girl at the restaurant I ate at last night whether she liked living where and she said she did. Maybe it’s not too dissimilar to where I grew up: a very happy place for young children, not so much for teens.

At the top of the hill, follow the road to the left towards the elementary school. Decorated totem poles near the school announce travellers’entrance into Lijia (or exit in my case).

10:17 – Not far out of the village, you have a choice to make. You can turn left and take a shortcut up the Maple Viewing Trail, or you can head right and either stick with the road, or take the slightly longer route incorporating the Romantic Cave Trail. Having already explored the latter on my post-breakfast wander, I went left, opting for the shortcut.

Wooden steps zigzag steeply up through the trees, but in March, the maple trees were decked in their spring colours.

10:28—At the top of the steps, the trail takes a left turn to follow the road. But if you’re interested in local culture, you might want to backtrack about 200 metres to visit the tribute stone.

This large, flat-topped rock sits beside the road, and according to the information board beside it, locals selected it as the spot on which they would leave offerings to the village’s protective god as they pass through. Judging by the amounts of various types of offerings, Lijia’s deity is particularly partial to cigarettes and betel nuts.

After checking out the tribute stone (and leaving a couple of sweets on it as a thanks for my easy and safe passage the day before), I returned to pass the top of the Maple Viewing Trail and continue on my way towards Dabang.

I found a made in Taiwan knife beside the road.

I passed a few small farms, but the road is so quiet that you can hear cars coming for miles, giving you a kind of audio map of where you’ll be in a little bit.

In one of the tea fields, there was this giant rock. It had such a presence to it that I found my eyes gravitating to it whenever the road afforded me a clear view.

As the road climbed further up, I could see that the boulder sat in the middle of the tea field with tea pickers’ paths radiating out from it as if the rock were some kind of spider in the centre of a web.

Much of this day’s walking was done under the shade of sweet gum trees. They have tri-lobed leaves and drop their seeds in spiky balls that are about the size of a big marble. This tree holds great significance to the Tsou people who live in Alishan’s tribal villages. According to the Tsou origin story, the first god, Hamo, came down from his home on Jade Mountain and rattled the boughs of a sweet gum tree, sending the leaves drifting down to earth. Those leaves became the ancestors of today’s Tsou people.

Hamo is also used to explain why the Tsou live where they do. At first, the people spread widely throughout the lower slopes and plains, but when a huge flood hit the land, everyone retreated upwards and inland towards Jade Mountain. As the floodwaters receded, Hamo—who is depicted as being human-like in form, but with especially big eyes—left the safety of the summit to walk through the land and survey what was left. Where his feet fell, the water-softened earth was flattened and these depressions became the locations of the Tsou’s villages. Tefuye—the oldest village—was said to be the first of those footprints.

Although the road felt quite long, I was content with just my own thoughts and the sights and sounds of nature for much of the journey. There was plenty to enjoy looking at, like the black jacks and brambles (some of which had soon-to-ripen berries swelling from their spiny tendrils). Birds were abundant too. I saw rufous-faced warblers (above, right), collared finchbills, Steere’s liocichlia, white-rumped munias, emerald doves, and vivid niltavas, and while I didn’t see them, the sound of white-eared sibias and Taiwan barbets were a constant companion.

12:46 – At some point, the climbing turned to descending, and I found myself heading down through a valley full of tea farms. There were more people on the road by this point. Some of them were farmers, but many were holidaymakers returning from their weekend stay in Lijia.

Near the entrance to one farm, I met this dog. It ambled over to me with the loose tail-way and relaxed stance that indicated it was in the mood to make friends, and so we had a brief greeting. Then a man on a blue truck came from the farm and shouted at the dog telling it to go home. The dog set off after the vehicle, but at a very leisurely pace, and it accompanied me for the next two kilometres.

While I was admiring the view here, the dog took a shortcut through the tea and I thought he’d given up on waiting for me…

…but upon rounding the bend a few minutes later, there he was!

After a while, my friend picked up another friend, and so the three of us carried on walking downhill. This pair is evidently much used to doing things at their own speed and as they wish, because their route meandered all over the place with many pauses to explore intriguing-smelling animal paths.

Then they must have arrived at the first dog’s home because they stopped outside a farm, and I was on my own again. I could have used their support a little later, because it was just after they left me that I encountered the two most ferocious guard dogs of the walk so far. Maybe that’s why they didn’t want to come any further.

The road does a series of right squiggles through a hamlet, and the road’s retaining walls are adorned with artwork depicting the legends of the Tsou. One showed Hamo shaking the sweet gum trees, and another shows the tale of how the Tsou learned to work leather. According to that story, all the Tsou elders knew that one of the deer in the forest was a deity. That deer was identifiable by its impressive size, and hunters were forbidden from harming it. But as is always the way with these stories, a youngster thought he knew better. He was out hunting with his brother when he saw the sacred deer, and despite a warning from his brother, shot the animal with his bow and arrow. In retribution, the injured god-deer picked up the boy, hanging him from the branch of the tree and tugged him back and forth, tanning his skin. The deer then instructed the remaining brother to run back to the tribe and tell them what had just occurred. The brother did so, and this is how the Tsou learned to tan hides. If you take a look at the demonstration house in Danayiku, you can see a hide tanning branch strapped up to one of the central supporting poles. It needs two people, one standing on either side to work the skin back and forth.

As I was stopped to watch a farmer raking over furrows in his ginger patch, the group of nurses from Tainan that had been staying in the B&B with me last night drove by in three cars. All of them slowed and told down their windows to wish me well and I felt like royalty!

For more on Taiwan’s ginger cultivation, you might want to check out this informative article from Micheal Turton in the Taipei Times.

As I drew closer to Dabang, the scenery just kept getting prettier and prettier.

The Zengwen River flowed through the valley to my left, and high up above it I could see the red arch of Fugue Bridge up on Provincial Highway 18 (the one that goes up to Alishan National Forest Recreation Area). Another shift in the sound and scenery came when I heard the first cawing of a crow.

15:00 – More artwork marked my arrival into Dabang (達邦 also written as Dapang, and known as Tapangu in the Tsou language), and before checking in, I headed down past the old Japanese police dormitory to the Tsou Cultural Exhibition Hall to stamp my trail passport. The police station was one of many such outposts built in Taiwan’s mountainous regions to suppress, monitor and observe the local aboriginal people during the period of Japanese rule.

This stamp is kept in the entrance of the Tsou Cultural Exhibition Hall.

And the exhibition hall is situated between the village’s school and the school’s sports field.

I had a look around the exhibition hall before finding my way to my place for the night. The ground floor has artifacts like tools and clothing, while on the upper floor, there are some models showing food preparation and storage facilities, as well as a lot of photographs and documents showcasing the tribe’s intangible cultural heritage.

My homestay for the night was clean, quiet and moderately comfortable, but it had two huge bonuses. One was the bathtub that I immediately used to draw a cold foot bath to try and ease some of the road-weariness, and the second was that it opened onto a balcony with a view over the village. It also just so happens to be a minute’s stroll from another tasty aboriginal restaurant. I know I am missing out by being vegetarian. The barbecued meat options looked and smelled amazing.

After dinner, I went for a brief stroll through the village to find the convenience store, where I picked up some tea and a beer before turning in for the night.

GETTING THERE

GPS location:

- Start point – N23 24.255 E120 43.220

- End point – N23 27.215 E120 45.000

Accommodation:

Staying in Lijia – There is one well-known hikers’ accommodation in Lijia, as well as a few campsite options. I stayed in the former. It provides breakfast and will help you book dinner at a nearby restaurant for an extra fee ($300).

- Name in Chinese: 嘉娜百藝工坊

- Address: 605嘉義縣阿里山鄉里佳61號

- Contact: 052511383

- Cost: $2,400 for a double room including breakfast. (Dinner can be pre-booked nearby at the time of booking.)

- Booking methods: telephone

- Clothes drying facilities: There is a spin dryer and a place to hang up your clothes.

Staying in Chashan – There are quite a few options in Dabang and Tefuye. I have to confess that price was my main consideration in picking this location, but it was perfectly OK.

- Name in Chinese: 青秀芳山莊

- Address: 605嘉義縣阿里山鄉達邦村1鄰14號

- Contact: 052511018

- Cost: $800 for a room with one double and one single bed (although I think my price was for single occupancy). This place doesn’t provide breakfast.

- Booking methods: telephone

- Clothes drying facilities: There is a spin dryer and a place to hang up your clothes.

MOUNTAINS TO SEA GREENWAY DAY 7 TRAIL MAP

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)