MSTW SECTIONS 06-08

On day two of the MSTW, I left the Inner Sea Trail section and continued onwards to the Canal Trail portion. It was another easy bike ride through landscapes that became increasingly less urban and industrial, and more rural and agricultural landscape.

MSTW PASSPORT STAMPS: There’s one stamp to be collected on this section. It can be found at the entrance gates to Wushantou Reservoir (烏山頭水庫). The gates are open daily, 8am-5:30pm. Visitors need to pay to enter, but if you’re only stamping your passport, you do not need to pay.

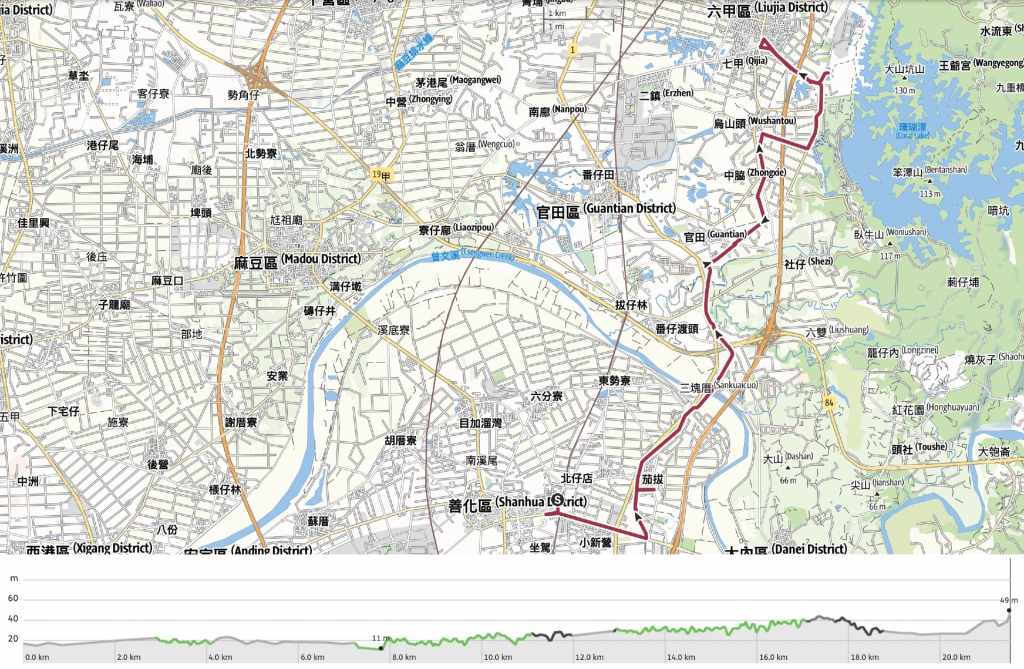

DISTANCE: 21.5 km – This doesn’t include travelling from the centre of Shanhua to the starting point or from the YouBike stand in Liujia to Zhennan Temple.

TIME: 3 hours from where I picked up the trail to where I left it. However, if you include the time it took to get to and from accommodation at either end of the day, then it was probably closer to 4.5 hours.

TOTAL ASCENT: About 70 metres.

DIFFICULTY CONSIDERATIONS: This is a super short, super easy day.

FOOD, DRINKS & PIT STOPS: I left Shanhua with 1 litre’s worth of full water bottles thanks to the train station water dispenser. Shortly into the journey, you can top up again at Jiaba Tianhou Temple. After that, you will need to detour into Liujia for supplies. I got dinner in Liujia, and made sure to also pick up the next day’s breakfast from a convenience store before heading to the temple where I planned to spend the night. If you stay at the same place, I strongly advise you have breakfast ready to go so that you don’t waste time trekking into Liujia and back the following day.

TRAIL SURFACES: All well-surfaced bike trails or roads.

SHADE: Little to no shade the whole way. For sun-shy folks, make sure to have a hat, long sleeves, and gloves.

MOBILE NETWORK: Clear throughout.

SOLO HIKE-ABILITY: No problem at all.

OTHER: This could easily be combined with day one if you’re looking to shorten the number of days spent walking.

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map, GPX file and all the other practicalities. Or, for a video version of this post narrated in real-time, you can watch this video.

DETAILS & DIRECTIONS:

Unsurprisingly, given the less than salubrious nature of my accommodation, I did not have an especially good night’s sleep. I woke up at 6, then drifted on and off until my alarm went off after which I set about getting dressed and ready to leave. It had rained heavily the night before, but there were no signs of clouds as I made my way to a breakfast store.

08:30 – I found a little roadside vegetarian breakfast stall where I had a flaky pancake made by a lady who asked me about my travel plans as she prepared it.

9:23 – With food inside me, I walked back to the railway station to pick up a YouBike. There were other bike stations I could have used, but I knew I’d be able to top up my water bottle in the station, so I thought I would kill two birds with one stone. From there, it was another 10-to-15-minute ride back up the road to where I’d left off the day before. Along the way, I cycled past the Taiwan Beer brewery, the oddly pleasant yeasty scent of it just reaching me over the morning traffic fug.

The path meanders through farmland for much of this day’s ride.

And for the majority of the day, it crisscrosses Chianan Big Canal.

9:33 – An MSTW sign placed outside this building says it’s a trail workstation, but since I’d just set off and wasn’t in need of anything, I didn’t pop in.

9:46 – A sign placed at one of the points where the bikeway intersects with the road indicated that just a few minutes away, I could find Shanhua Jiaba Tianhou Temple (善化茄拔天后宮), so I turned right to follow the road. I’d actually visited this spot before when I’d attended a group trip to some highlights of the MSTW with the folks from Taiwan Thousand Miles Trail Association. It’s funny how different places can feel when you walk or cycle between them rather than drive. this time, riding into the temple courtyard, I got a much stronger sense of its presence as a community hub. A couple of vendors had set up their trucks in the forecourt, and locals were sat in the shade of trees to chat in the midmorning breeze.

Also in the courtyard, you can find the preserved remains of a well that is said to predate the temple itself (I’ve seen it reported as having been dug in 1660). It was covered for some time but has since been preserved in such a way that visitors can observe it, and now, at Dragon Boat Festival, locals can once again participate in a tradition called “Drawing Noon Water” (取午時水). This practise harks back to the old folk belief that water collected between the hours of 11 in the morning and 1 in the afternoon on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month has the power to cure ills and ward off evil. Right beside the well, you will find a plinth bearing a statue of Koxinga (鄭成功), a Ming dynasty general who is hailed as being responsible for sending the Dutch packing from Taiwan. Despite not having resided in Taiwan for very long (less than a year) and not having travelled far beyond the boundaries of Tainan, legends of Koxinga’s miraculous exploits abound. Following his death in 1662, temples dedicated to him began to proliferate, and even more found space for him on a side altar.

Tianhou temples are all dedicated to Mazu, an islander turned sea goddess much beloved by the seafaring ancestors of Hokkien-speaking Taiwanese folk. Her temples can be found all over Taiwan and many of them have long histories. The Jiaba Tianhou temple is a case in point. According to local historians, the first iteration—a thatch-roofed structure—was built in 1661 by an immigrant from Meizhou who carried the deity with him as he sailed to a new land. Other versions say the Koxinga himself brought the temple’s founding deity over, along with a sister statue now enshrined at Luermen Tianho Temple (鹿耳門天后宮). Whether or not there’s any truth to this celebrity origin story is beyond my capabilities to decipher, but it’s certainly true that the two temples remain connected through a four-yearly pilgrimage.

When I popped in, a sacrilegious sparrow had taken up residence on a spot above the altar and was singing its heart out as merrily as if all the incense and decoration was in its honour. I also particularly enjoyed the characterful depictions of Mazu’s twin guardians, the All-Seeing General (千里眼), his green hand raised in front of his face, all the better to help him spot impending dangers, and the All-Hearing General (順風耳), red finger pointing to his exceptional ears because there’s no sign to indicate being able to hear impressive distances (the obvious cupping a hand to the ear would more likely suggest trouble hearing). The temple has antechambers to both sides and in the one to the left of the main hall, you can find the palanquin and deities that get sent out on special parades.

Heading back to the trail, I cycled along a path shaded with giant-leafed trees, and I caught my first glimpse of mountains rising in the distance. None of them were Jade Mountain, and it’s an odd feeling knowing that (if all goes to plan), I will soon walk myself higher than the highest of them.

10:25 – Where the trail crosses over Zengwen River, there is a confluence of bridges. The one that I rode over now carries pedestrians and water, the one on the left carries cars, and the stump of the middle one, (the original Zengwen River Aqueduct), has been left mostly in situ to remind people of the region’s early irrigation infrastructure. Completed in 1929, and decommissioned in the 2010s, this was an impressive feat of engineering for the time, providing traffic access and water for people living south of the river. Water was conveyed along its 339-metre length through a boxlike channel (as seen here in an old photo), which had a pedestrian and vehicle deck laid above it. The end that is still connected to the road is open, so if you fancy taking a stroll along this historic structure, you can do so.

Continuing onwards, the bikeway flies along a raised route sandwiched between the canal and farmland.

Sometimes it hews closer to the roads, at other times, it’s just you and the duck farms.

10:58 – After passing through a small village, the bikeway turns right and merges with Batian Road.

The road passes farmland and a village or two. The road is lightly trafficked, and at the time of my visit, the trees lining it were decked with bright pink-purple blossom.

11:14 – Keep an eye out for signs directing you to turn left off Batian Road and through farmland full of (I think) fruit trees, maybe longans or lychees.

Egrets and black-winged stilts doing their thing.

11:28 – The path reaches a junction beside the sluice gate which splits Jianan Big Canal from Jiabei Big Canal. Here, the MSTW finally takes its leave of the canal bikeway and strikes off to the right, following a larger, broader waterway up towards Wushantou Reservoir.

A couple working in a submerged field. I’m not familiar with the look of this plant, but if I had to guess, I would think it might be water caltrops since nearby Guantian District is well-known for growing this devil-esque crop.

11:40 – I finally diverted away from the canals when I reached this plaza marking the spot where the flow barrels out of the reservoir’s channel on its way to irrigate the farmland of the planes. Signs in the vicinity introduce Yoichi Hatta, the Japanese engineer who was responsible for overseeing the construction of this canal network, and therefore bringing water to all those who needed it. Hatta, who arrived in Taiwan in 1910, having not long graduated, lived in Taiwan until he died in a ship that was sunk by American bombers.

Even in death he has remained close to his proudest achievement-he is buried beside Wushantou Reservoir. His wife is buried with him. Rather tragically, she died by drowning herself in the reservoir after World War Two ended in defeat for the Japanese. Human interest aside, Hatta’s contributions to Taiwan’s hydro-engineering landscape are impressive, and to this day, the network of waterways he created is the biggest irrigation network in Taiwan.

11:48 – Turning left (back) onto Batian Road, I soon found myself outside the entrance to Wushantou Reservoir Scenic Area. Visitors can pay to enter and enjoy the scenery, but if you are just interested in walking the MSTW, you can find another of the trail stamps here. (And my hosts at the temple told me that locals sneak in via the back entrance provided by Liujia Zhennan Temple Trail because that way, they don’t need to pay.)

The stamp is located just inside the gates, fixed to the wall of one of the ticket booths. No one paid me any attention as I stamped away.

Disney characters adorn a gate beside the road.

12:07 – Follow the road until you hit this junction with a large memorial (or grave). The MSTW continues right past graves and soon reaches the foot of the road leading up to Liujia Zhennan Temple.

12:13 – This was to be my bed for the night. I dropped in to figure out who I needed to speak to, but the day was still early, so after dumping some non-essentials, I headed into Liujia for coffee, snacks, and some time-wasting.

I ambled around the town for the afternoon, enjoying a coffee (and an ice cream) before visiting a vegetarian restaurant for dinner.

Dinner was noodles with soup and greens. Once sated, I made my way back along the road in the direction of Liujia Zhennan Temple. Along the way, a guy on a scooter passed me and then circled back saying, “Hellooo! Helloooo! How are you? I can help you.” He would be the first of many, many, many concerned locals offering rides and assistance over the following days.

Once I arrived back at Liujia Zhennan Temple, I met Lin Rong-hui (林榮輝), the temple’s founder and manager. He told me that he’s been managing the temple for decades, and so I mentioned that I was curious to hear about its origins and how it came to offer a “sleeping with Lü Dong-bin” experience. What followed was one of the strangest, most deeply Taiwan-flavoured evenings I have experienced.

Mr Lin, his Mandarin heavily accented with Taiwanese, invited me to a room in front of the temple, saying that most evenings, he and whoever was around would sit out and have tea there. I sat down, watched as Mr Lin ceremoniously prepared the first of many pots of tea, and over the following few hours, was entertained by a rolling collection of characters.

After listening and chatting, I found out that only a couple of the crowd were regulars who often visit the temple of an evening. Another guy worked at the nearby Industry Technology Research Institute Foundation and said he spends every Tuesday evening here to perform reflexology massages on whoever happens to be around. The massages seemed especially intense and perhaps somewhat spiritual in nature because the process seemed to involve the masseuse emitting numerous loud belches of the kind that you sometimes hear someone making when they are communicating with deities. Three men had their feet prodded, scraped and pummelled, one of which was the foreman of some type of construction project in the vicinity. He said he had never had such a massage before and the poor guy was used as a test subject for the reflexologist to show me how to relieve muscle aches later in my walk if necessary (run a finger down from where the second toe joins the ball of your foot all the way to the heel-end of your arch, then press hard). When it was Mr. Lin’s turn, I was invited to comment on the sculptured beauty of his calves—evidently, they are pale and shapely as only those of an educated man can be. When asked, I declined the opportunity to sit in the massage chair myself.

Later, a trio of people who would be spending the night in the same chamber as me arrived. It was a chatty woman who introduced herself using her nickname of Little Cat as well as her sister and (kind of) boyfriend. She later seemed to take much delight in confiding to me that he was a lot older than her. These guys brought food, beer, and more tea, which they passed around freely. A little later, two more women turned up. One seemed like a returning regular—a Chinese woman who said she had once slept in the Lü Dong-bin chamber and somebody, maybe Tudi Gong, maybe Lü Dong-bin appeared to her and smiled. The other woman was Liu Cai-ni (劉釆妮), a reporter who runs a news site, Facebook page, and YouTube channel dedicated just to religious happenings. Mr Lin had asked her to make the trip over to speak to me about the temple.

Over the next hour or so, Lin and Liu told me (and the rest of those present) some stories about the temple and its origins. One included the illegal capture and killing of a snake. According to Lin, the trail behind the temple was commissioned in 2007. The land here was full of graves and had long been known by those running the temple to house lots of “spiritually powerful” animals, specifically snakes. So, when the construction workers began work, they were warned not to interfere with he wildlife. One day, Lin saw one of the workers clutching a snake-catching bag, and reminded him of the fines associated with the illegal ensnarement of wild animals. The man promised not to catch anything, but unbeknownst to Lin, the bag already contained a snake, and the snake thief snuck back down the mountain with his bounty while Lin said he was taking an afternoon nap.

In his dream, Lin suffered something like a stroke and was totally unable to move normally. After consulting a pharmacy to little avail, he turned to spiritual assistance only to find that the deity Wangye (王爺) had put a bounty on his life and that he should run for it. And so in his dream, he ran and ran, up the hill behind the temple until he came to a place with a couple of pools. The shock of the cold water startled him, as did the snake he found there, and with that, he realised that Wangye was out to get him because someone had killed one of the powerful snakes that resided there.

After waking, Lin found the man and confronted him. The man admitted his crime with a shrug, saying, “What else was I going to do? It was a 400-gram snake—snakes that big don’t grow on trees.” (I’m paraphrasing, obviously.) The best course of action would have been to return the live creature to the hill, but the snake gone and turned into snake stew, Lin had to find another way to appease the snake spirits and stave off further horrible dreams or ill health.

In the past, the temple also used to offer another type of dream-related service. If requested, it would send a deity and a medium to a believer’s house to spend the night. Believers could ask the deity for advice, which it would dispense via the medium’s dreams. As far as Mr Lin knows, they were the only temple in Taiwan to offer this service, but the medium is now in his late eighties and there’s no one to take on the role.

Exhausted from hours of conversation, I finally turned in for the night with Little Cat and her companions. Very sweetly, they insisted on waiting for me while I brushed my teeth because they didn’t want me feeling scared by walking back alone.

GETTING THERE

Shanhua has a few YouBike stands, but currently, there’s only one in Liujia (using the YouBike app is the best way to find these). Additionally, the one in Liujia is about a 2-kilometre walk from the trail and Liujia Zhennan Temple (the second night’s accommodation). This means that once you park your bike, you’ll have to walk back up the road to rejoin the trail.

GPS location:

- Start point – N23 07.520 E120 19.525

- End point – N23 13.760 E120 30.120

Accommodation:

Staying in Shanhua – I wouldn’t exactly recommend this place, but there aren’t many options in Shanhua. The bed was very hard and the cleanliness of the facility was dubious to say the least.

- Name in Chinese: 富賓旅社

- Address: 741台南市善化區中山路339號

- Contact: 065837159

- Cost: $700 (I think this is the price for a 2-person room)

- Booking methods: telephone

- Clothes drying facilities: There’s a washing line, but no spin-dryer

Staying in Lijia – Despite not getting much sleep, I absolutely loved the chaos of the evening spent at this temple, and I’m really glad that I included a temple stay on this journey, it feels like an important part of Taiwan’s low-elevation multi-day hikes. If you’re not fussed about staying in “the god room,” you can always opt for one of the more standard beds. For help booking a room at Liujia Zhennan Temple, you can click here.

- Name in Chinese: 六甲鎮南宮

- Name in English: Liujia Zhennan Temple

- Address: 73445台南市六甲區工研路2號

- Contact: 066982464

- Cost: $600 for a cubicle in the Sleeping Fairy Dreamland

- Booking methods: telephone

- Clothes drying facilities: I think there was a spin-dryer, but I didn’t use it

MOUNTAINS TO SEA GREENWAY DAY 2 TRAIL MAP

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)