RAKNUS SELU TRAIL – SECTIONS RSA56 – RSA58.2

In December of 2024, I embarked upon my final two-day stretch on the Raknus Selu Trail’s main A route. Due to weather and work constraints, hiking it in sections like this took me the better part of two years, but perhaps that’s no bad thing, the extended time frame has allowed me to really take my time getting to know each section and exploring all the towns and villages the trail passes through along the way. If walked in a single through-hike, the section covered here would count as day thirteen — a gentle day spent following mostly rural roads between the Hakka town of Zhuolan and the Tayal village of Shuangqi.

RAKNUS SELU STAMPS: The trail stamp for RSA57 is kept at Baibufan Farm Shop. Google’s opening hours suggest that it’s open daily until 4:30 pm, but I would be surprised if that were correct.

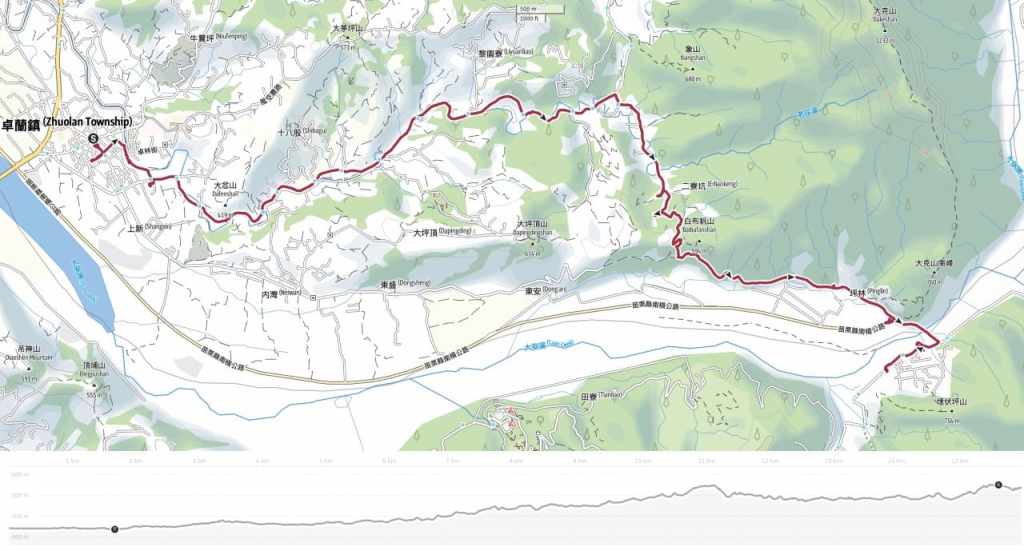

DISTANCE: About 16 kilometres.

TIME: We walked this in a comfortable 5 hours.

TOTAL ASCENT: About 320 metres, although it didn’t feel like we did a whole lot of climbing.

DIFFICULTY (REGULAR TAIWAN HIKERS): 2/10 — The distance is the only slightly difficult aspect of this walk. The pathfinding, climbing, and everything else is all pretty straight-forward.

DIFFICULTY (NEW HIKERS): 3-4/10 — Even someone new to hiking in Taiwan shouldn’t find this to be a challenging walk.

FOOD, DRINKS & PIT STOPS: We took about 1L each and drank most of it on a sunny winter day. Foodwise, there are plenty of places to stock up in Zhuolan, but after that, there aren’t any places to resupply until you arrive in Shuangqi. The village has a breakfast shop and one or two small restaurants, but they’re the kind of places where you have to ask to see what’s still available and if you’re vegetarian, you’re going to want to make sure you take dinner with you. We carried snacks and lunch for two days from Zhuolan, and I took emergency pot noodles for dinner. There is one possible coffee shop part-way along the walk, but it was closed on the day of our visit despite Google saying it was open.

TRAIL SURFACES: Mostly rural back roads with a short section of farm track and an even shorter section of trail.

SHADE: Most of this day’s walking is exposed to the sun. I managed to get a sunburnt nose even though I’d used suncream.

MOBILE NETWORK: Network coverage was good.

SOLO HIKE-ABILITY: This should pose no problem for solo hikers.

SECTIONS COVERED:

- RSA56: Zhuolan → Miaoli District Road 55 → Gongliaokeng → Tiaosha Historic Trail Trailhead (卓蘭 → 苗55 → 工寮坑 → 挑沙古道口)

- RSA57: Tiaosha Historic Trail (挑沙古道)

- RSA58.1 Tiaosha Historic Trail → Miaoli District Road 58 (挑沙古道 → 苗58)

- RSA58.2: Miaoli District Road 58 → Baibufan Bridge → Shuangqi → Xiachuanlong → Chuanwu Ai Yong Historic Trail Trailhead (苗58→白布帆大橋→雙崎 → 下穿龍 → 穿霧隘勇古道口)

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map and GPX file and all the other practicalities.

DIRECTIONS:

We stepped off the bus from Dongshi right in front Elun Temple (卓蘭峩崙廟) and beside a couple of shops selling these odd triangular metal contraptions. We couldn’t know it yet, but those contraptions would be a symbolic item for this final two-day stint on the RST.

We popped into the temple to see if they had somewhere to top up our water bottles (if there was somewhere, we didn’t spot it) and pay our respects before heading off to gather provisions for the upcoming two-day walk.

The pull of the market street was irresistible. We moseyed around the whole loop, admiring the tea-pickers’ balaclavas and grabbing a bag of boiled water caltrops to snack on. The vendor said she had sold four huge vats already that morning, and when she finished the next one, she wouldn’t have any more to sell until after the new year (for context, we visited in mid-December).

We wandered slowly through the town, stopping at a tea shop (to fill up my flask with green tea), a 7-Eleven (to get emergency pot noodles for me, and tea eggs and whisky for Teresa), and a bakery (to get fuel for the following day).

With all our provisions sorted, we finally made our way to the town’s western edge, where we met Laozhuang Creek — a waterway that would remain our companion for most of the day’s walking. Just as we were leaving the town behind us, we passed Shangjiao Fude Temple (上角福德宮), a small land god temple shaded by a trio of sprawling banyans. In fact, I spotted the banyans way before we even reached the temple — the large dome of their conjoined canopy stands out amidst the town’s low-lying dwellings. The largest among the three is thought to be over 200 years old and has its own incense burner — as we watched, a woman came to offer it a stick of incense.

Heading onwards, we saw a family fishing and passed a couple of other people out for a morning stroll, then just before we reached the red bridge, a woman on a bike road up and asked us which section we were walking. It was clear that she knew we were Raknus Selu hikers, and as it turned out, she should know better than most, since Ms Qiu was one of the Zhuolan section’s volunteers.

She leant her bike on the bridge and accompanied us as we walked up the road to Zhuwei Fude Temple (竹圍福德祠).

At the junction, she explained that we needed to turn left and keep following the river, but as I was snooping around the temple, Teresa’s offhand remark that I liked the traditional sanheyuan-style houses led to an offer to see a nearby historic house.

And so — within minutes of setting off — we were waylaid to go and explore the lovely ancestral hall of the Zhan family. The Zhan’s are the largest familial group in Zhuolan, with around a third of the town’s population sharing this family name. They began immigrating from Raoping County (饒平縣) in Chaozhou Prefecture (潮洲縣) southern China some 250-odd years ago, and a large number of them ended up settling in Zhuolan. The Zhans were mostly Hakka folk, and as such, Zhuolan has become a stronghold of Raoping Hakka language and culture.

We were introduced to one of the current owners of the massive housing complex, who happily showed us into the ancestral hall while apologising that she didn’t have as much historical knowledge as her husband who was off on some errand. Inside, she showed us the ancestral tablet on the altar, saying that she has forgotten precisely which generation she belongs to but that it’s the 20-somethingth. She also pointed out that their altar is different to usual because the god occupies a spot on the righthand side of the ancestral tablet as opposed to the typical lefthand spot. She said that everyone who knew why the altar is arranged this way is long dead, so it is now just a family mystery. I think plenty of families have their small ancestral puzzles — Teresa’s family has an extra family named on their tablet and their senile grandmother is the only one alive who knows why its there, and the secret will go to her with her to the grave.

Above one of the doorways, there was a black and white photo showing rows of sombre-faced Zhan familiy members in traditional Hakka attire. The woman told us her deceased grandfather had hung up. He died at the ripe old age of 92 some years back, but even so, he hadn’t been born when the photo was taken. Looking closer at the picture, it’s possible to make out the characters above the doorway to the ancestral hall — the scene has barely changed at all.

Returning back to the junction with Zhuwei Fude Temple, both Ms Qiu and Ms Zhan made sure we had enough water for our travels and sent us on our way. Right from the start, the scenery set out its stall. We began passing field after field of strawberries and oranges — landscapes that would carry us all the way from Zhuolan to Dongshi.

A roadside board full of CCTV-captured photos of a fly tipper. Unfortunately, it seems this method is not particularly effective since in the newest photo, you can see the three older photos already on the board. We passed several of these shaming boards along the walk as well as plenty more signs requesting that people don’t dump their rubbish beside the road. We also came across ample evidence of people ignoring these requests, like a long stretch where the smell of fermenting rotten grapes was so overwhelming that I could barely breathe. It never ceases to shock me just how callous farmers can be about the environment — surely anyone who makes a living off the land would be invested in ensuring the continued health of said land.

Under a clear blue sky, we followed increasingly quiet roads gently uphill along the course of Laozhuang Creek. Much to Teresa’s entertainment. each and every scooter rider or truck driver we passed stared at us (or rather me) as if I was an alien, which, I suppose I probably am in these parts — one even shouted a very happy hello at us.

From a bridge, we spied a farmer tending to his orange crop. He heard us talking and looked up to ask what we were doing. Teresa told him that we were walking and he humphed, clearing deeming our endeavours to be too foolish for further comment.

At the far end of Xiangshan Second Bridge (象山二橋), we were just getting ready to turn right and head through the village of Xiangshan when a guy on a scooter pulled up. It was the hello shouter from earlier and he had come bearing gifts. He handed both us bottles of sports drinks and dry noodle snacks, saying that he saw us walking up this way and was worried we didn’t have enough provisions with us. Speaking to him, Teresa instantly picked up from his accent that he was Indigenous — from about Nanzhuang onwards along the RST, there are small pockets of Indigenous populations, although for the most part, I have not noticed them until these two final days when some of the villages we passed through seemed to be home primarily to Indigenous groups. We had a little chat and he and Teresa enjoyed a brief karaoke session as they belted out the words to a Canto pop song that was blaring from a speaker on his scooter, then, after an obligatory photo together, we set off again.

After passing through a small collection of houses, the road reaches a T-junction. We took a left here.

You’ll know you’re heading in the right direction when you spot the bright red and white paint of Xiangshan Fude Temple. As with the majority of the land god temples we passed in this area of Taiwan, both Tudi Gong and his wife can be seen on the altar.

Orchards and farm buildings dot the landscape.

The further off the main road we went, the narrower and rougher the track got.

Eventually, we left all the farm buildings behind and the track zigzagged up to a junction. We followed the RST signage directing us to the right and walked towards a field where a row of workers were spreading bone meal over freshly tilled land. Just before we reached them, the RST veered right again and we started to climb Tiaosha Historic Trail (跳沙古道).

You wouldn’t necessarily know it based on how the path looks today, but this was previously an important thoroughfare between the villages of Xiangshan and Baibufan. The latter sits on the banks of Da’an River, a broad sweeping channel with abundant gravel and sand — important house-building materials. Xiangshan’s villagers would head over to Baibufan to collect sacks of sand which they would then lug back over the hills, giving rise the name “Tiaosha Trail” (literally “picking sand trail”). Today, people are still using gravel from the riverbed, except these days it’s transported by huge lumbering trucks that kick up long tails of dust as they drive up and down the riverbanks.

In one section, the original trails seems to have been wiped out either by time or maybe by a landslide and a new trail cuts steeply downhill to join Baibufan Industrial Road.

An interesting sculpture of wood and metal — perhaps referencing the region’s agricultural heritage — marks the southern trailhead.

From there, we turned left onto the remains of Baibufan Industrial Road. (This is where someone had dumped large volumes of rotting grapes.)

At the end of the track, we merged straight onto a more established-looking road and followed that into the small village of Baibufan.

On the outskirts of the village, we passed another land god temple — this one with a dragon stone lurking in a cave behind the main temple. The village proper is little more than a small gathering of houses, and almost all of the residents seemed to be sat outside chatting. Elderly folk were gathered in small huddles of mobility scooters and a couple of younger people were seated around a fire and a sound system that was belting out karaoke hits.

Heading onwards, the RST goes straight over Baibufan Bridge, but first, we took a right onto County Highway 149 to go in search of the next RST stamp.

Carambola King stands at the junction overseeing the traffic — the region is apparently known for its production of starfruit (not that we spotted any starfruit trees).

Other roadside decorations underscore the merging of Han and Indigenous culture in the area — wild boar, persimmons and grapes adorn the boundary marker between Tai’an and Zhuolan Townships.

The stamp is kept in a roadside farm shop selling pumpkins, plump radishes and baskets of sweet potato leaves. It depicts a leopard cat — a rather cute endangered species that can still be found in the hills of Miaoli.

Retracing our steps, we walked over Baibufan Bridge. Looking upstream gives some lovely views of the Da’an River Valley. The river serves as a natural boundary between Miaoli and Taichung, so by the time we reached the far side, we were in Taichung.

At the far end of the bridge, we turned left and began the final ascent of the day.

The road eases you into Shuangqi Village (雙崎or Mi’ihuo), a Tayal Indigenous village with a population of around 1200. Signs that you’re entering a majority Indigenous area are few, but they’re there if you know what to look for: artwork, the Presbyterian church, and — most obviously — the reconstructions of traditional buildings.

We checked into our accommodation at about 4:30 and after a brief rest, went out in search of dinner. Teresa got lucky, the shop next to us had a steaming bowl of noodles for her, but your vegetarian writer here fared less well. I made do with the emergency instant noodles I’d brought with me and some snacks from the village’s convenience store.

Bellies filled, it was time for an early night in our cosy, wood-panelled accommodation. As seems to be normal for Indigenous villages throughout Taiwan, the night air was full of the sounds of barking dogs, and somewhere on the street behind us, a group of friends had gathered to chat and drink around a fire, but despite that, I was soon out for the count.

GETTING THERE

Public transport:

- Getting to Zhuolan — The 208 leaves Fengyuan train station bound for Zhuolan Bus Station about once an hour.

- Getting back from Shuangqi — The 253 service runs between Shuangqi Village and Dongshi Bus Station about six times a day with the last bus departing from in front of the school around 6pm (although since this is a rural service, it may come 20 minutes earlier than expected). Lots of buses (90, 206, 207, 208) shuttle backwards and forwards between Dongshi Bus Station and Fengyuan Transfer Station. Once you’ve reached Fengyuan, you can hop on a TRA train to wherever you need to be.

Accommodation:

Accommodation in Zhuolan – Zhuolan doesn’t really seem to have many (or—aside from seriously expensive places on Lixiping—any) accommodation options. Luckily, getting to and from Fengyuan (which has lots of options) is pretty easy.

Accommodation in Shuangqi — There are a couple of places to stay in Shuangqi. We stayed in a breakfast shop that doubles as a B&B, which turned out to be very comfortable. The place has a single room that can sleep up to four.

- Name in Chinese: 芭勒的

- Address: No. 89號, Section 2, Dongqi Rd, Shuangqi, Heping District, Taichung City

- Contact: 0905630261

- Cost: I paid $2,300 including breakfast. The cost feels a little steep for two people but if your group fills the room, it’s much more reasonable.

RAKNUS SELU DAY 13 TRAIL MAP

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)