After about a month between sections, I resumed my Raknus Selu journey with a three-day, two-night jaunt starting from Zhudong, passing through Beipu an the fantastic temple complexes of Lion Head Mountain before making my way into Sanwan. This day was the shortest of the three, and I’d finished walking just in time for lunch. The rest of the afternoon and evening was spent exploring the streets of Beipu.

RSA25.1 – RSA25.2

RAKNUS SELU STAMPS: I started this walk part way through section RSA25.1, so I did not collect any stamps on this occasion. (There is a stamp by Hengshan Station which you would pass if you were walking the whole of RSA25.1).

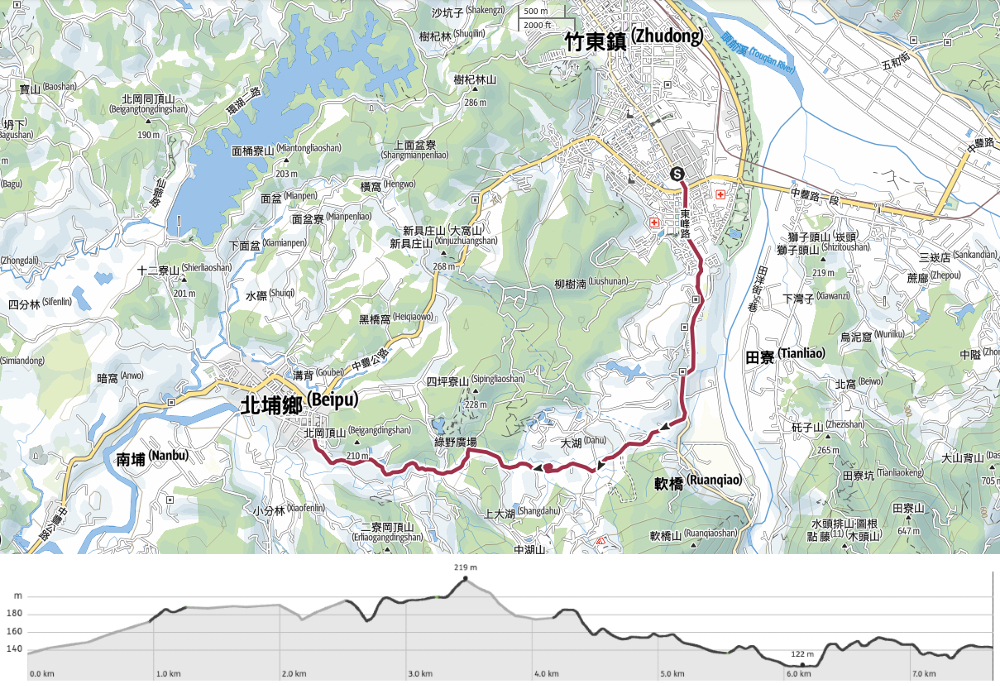

DISTANCE: 7.7 km – Originally, I had planned to start this day from Hengshan Train Station (which would have added on a couple of kilometres), but in the end, I decided to have a short day so that I could spend a little longer exploring Beipu.

TIME: About 2½ hours walking and a lot more spent wandering around Beipu.

TOTAL ASCENT: About 100 metres.

DIFFICULTY (REGULAR TAIWAN HIKERS): 1/10 – This is nothing more taxing than a short stroll along roads. There aren’t even all that many hills.

DIFFICULTY (NEW HIKERS): 2/10 – Getting comfortable walking along the side of a road is likely to be the most challenging aspect of this section if you’re new to Taiwan.

FOOD, DRINKS & PIT STOPS: There are established towns with plenty of places to buy provisions at both ends of this day’s walking, but nothing at all in the middle.

TRAIL SURFACES: The entirety of this day’s walking follows roads

SHADE: Much of this walk was quite exposed.

MOBILE NETWORK: Clear throughout.

SOLO HIKE-ABILITY: I think this is a pretty safe solo walk.

OTHER: I arrived in Beipu in time for lunch and found that half a day was just about enough to explore the town. If you prefer a more leisurely schedule with a little more time for rest, you might want to spend a whole day here.

SECTIONS COVERED:

- RSA25.1: County Highway 122 → Hsinchu District Road 39 (縣道122→竹39)

- RSA25.2: Hsinchu District Road 39 → Beipu (竹39→北浦)

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map, GPX file and all the other practicalities.

DETAILS & DIRECTIONS:

10:25 – I started the day’s walking a little earlier than anticipated when the bus driver kicked all remaining passengers off the bus one stop earlier than expected. I’m not sure why, because the bus carried on a little further, but whatever. It added all of five minutes to the walk. So, from Taiwan Cement bus stop, I followed Dongning Road south until I caught up with where I’d previously left the trail.

10:47 – When you get to the crossroads by the petrol station, head straight over. Actually, the road splits in two here, the RS follows Dongfeng Road, which is the right hand one. Dongfeng Road is the local street name for this part of County Highway 122. Before I went any further, I grabbed a coffee and a cheese mantou to keep me powering through until I arrived in Beipu.

There are a lot of breakfast and lunch box stores lining the road out of Zhudong, and when I passed through, in the golden 30 minutes between 10:30 and 11:00, there were many of both open.

11:04 – Knowing that the day’s walking would be short, I had plenty of time to visit temples and other diversions that piqued my interest. The first of these was Zhudong Yuntian Temple (竹東恊天宮).

The temple has two floors, with five altars on the ground floor and three on the upper floor-although the two outermost altars on the ground floor look a little bit like they’ve been fashioned out of repurposed space and furniture.

The top floor is worth visiting, if just for the artfully dramatic lighting (and snazzy neon tube lights). The Jade Emperor holds court in the central altar. In fact, since the right-hand altar houses the Three Pure Ones (三清道祖), maybe the Jade Emperor is represented twice since he is also one of the three. On the left is the regal-looking Queen Mother of the West (王母娘娘). This particular deity predates Taoism, (the earliest records of her date back to between 1766 and 1122 BC), but has been absorbed into the Taoist belief system over time.

I made use of the temple’s bathrooms before resuming my journey and was intrigued to spot the rather demonic graffiti that had been added to the hand-painted bathroom sign.

Almost as soon as I’d started walking again, a second temple caught my attention. This one had a dozy black guard dog and a table full of pineapple tops (but no pineapples).

It also had a four-faced Buddha with a whole army of elephants ranged around the four-sided altar.

Gradually, the buildings fizzled out and I found myself walking along the (non-existent) hard shoulder as huge trucks carrying gravel whizzed past. Thankfully, this only lasted for a short stretch, until I passed this gravel production yard, and after that things quietened down.

11:39 – In fact, it wasn’t much further beyond the yard that I left County Highway 122. At this junction, the RS takes a right turn and starts following Hsinchu District Road 39 as it winds over the hills to Beipu.

There isn’t much happening along the road, but I still found things to entertain myself. Like these idle siblings.

And this striking orbweaver spider. About ten minutes after leaving the larger road, I passed an odd mountain chalet village. Several huge wooden buildings were built on the right side of the village facing the graveyard that was on the left.

11:52 – The road crests a hill, then there are two junctions, one after the other. At the first, bear left, then at the second, take the right-hand lane. From here, the road starts to go downhill. Along the way, I passed a small land god temple with faded photographs on the walls and a glass of steeping tea leaves on the altar.

12:03 – Follow the road right at a mural depicting Dahu Community’s orange-growing industry. Along this next stretch, I passed a couple of houses with noisy guard dogs. The first pair did nothing but bark from the driveway, then a trio of handsome black dogs at the next homestead rushed out barking but then got all shy as soon as I approached.

Skinny betel but trees line both sides of the road, and even more dogs barked at me unseen from inside farms.

The road runs down to meet up with a stream and a little hamlet with several houses, then as soon as you’re past the houses, the road climbs again.

At a hamlet about ten minutes out of Beipu, I passed a house decked out with the kind of flowers and decorative boards that indicated someone in the family had recently passed away. The front room was packed with chatting relatives and a photo of an elderly man was on display.

When I arrived at the very outskirts of Beipu, a toothless old chap on a scooter pootled past me, stopped and yelled at me to get my attention. He said he’d seen me walking in Hengshan area a couple of weeks ago (which was possible, it was a couple of weeks ago that I walked Qilong Historic Trail. He then proceeded to try to introduce the core concepts of his religion to me (which seemed to involve a lot of flying around at night and not dying). In general, I tend to get a little defensive when people preach at me, but I am consciously trying to be my most open self on this walk, so I listened. After all, I was in no rush to be anywhere, and it didn’t hurt me to listen. As he talked, another local man walked past laden with groceries and stopped to join the conversation. Once he felt he’d told me enough, he presented me seriously with a laminated picture of maybe the sun or the moon and told me it would enable me to have wild dreams. The shopping-carrying villager and I were then both given a pastry and a jujube and the three of us all went out separate ways.

The road enters Beipu (which is also spelled Bebe, Peipu, and any combination of the above) at its southwestern corner, right beside a museum dedicated to sharing the life and works of photographer Deng Nan-Guang.

I went in and had a quick nosy at the exhibition. Deng was born into a wealthy Beipu family during while Taiwan was under Japanese control. Deng’s family was evidently able to prosper under Japanese rule, and Deng was sent to Japan to study—first as a high school student and later as an economics major. During his time at university, he joined the photography club and became involved in the New Photography Movement (a period in Japanese photographic history which spanned the 1920s and 1930s, and drew upon influences from movements in German artistic expression). In 1932, just a few short years after first picking up a camera, Deng had an image published in a photographic magazine, and from that moment on his work saw a string of exhibitions, publications and accolades. By the time he returned to Taiwan in 1935, he had made enough of a name for himself that he was able to establish his own photographic studio on Taipei’s Bo’ai Street (which is still to this day known as Taipei’s Camera Street). The same year, he began making trips home to document scenes from daily life in Beipu. Throughout his life, he was involved in numerous clubs and associations and worked with many groups, but the one constant was his body of images documenting life in Beipu, many of which can be seen in the museum. I was particularly fascinated by a series showing several festivals and cultural events. There was one entitled “還山” or “Return to the Mountain” showing a group of children following two men through a grassy field. It reminded me vaguely of the old UK folk custom of beating the bounds, although in reality, the two customs are very different. The “Return to the Mountain” procession is (was) a funerary ritual, while the UK custom was performed in order to maintain a collective knowledge of the parish boundaries.

13:03 – Hsinchu District Road 39 and the RS turn left to skirt around the southern tip of Beipu, and the following day, I would return to this spot to continue on my way.

From here on out, the rest of this post is no longer directions, instead, it is a collection of photographs and impressions from my time spent in this small Hakka town.

I still had some time to kill before I could check in to my hotel, so I headed to the only vegetarian shop that was open, Puyu Hakka Lei Cha. As well as selling the famous Hakka beverage that Beipu is known for (see below for more information), this store has a short menu of well-balanced vegetarian meals. I ordered sesame oil vermicelli noodles with medicine soup. The staff were able to communicate in English, and the store provides all guests with little sample sachets of their powdered teas to enjoy whilst waiting for your meal.

After lunch, I went for a little wander through some of the narrow back alleys in the east of the town, where all the historic buildings are gathered. One of the main reasons that people will visit Beipu is to experience Hakka culture. The town has been occupied by predominantly Hakka people for centuries and remains so to this day–consequently, the food, the architecture, are the way of life are all well preserved. The design of these streets is one such preserved element that signs in the vicinity draw your attention to. In the early days of Hakka residents settling here, there were frequent skirmishes between Hakka, Han and Aboriginal groups. These narrow roads with their many confusing twists and turns are designed to put an outsider at a disadvantage–something you can still sense now as lost-looking tourists peer around corners for some indication of which way to go.

The clear heart of this old town is Citian Temple (慈天宮), and its presence tells more stories of the region’s turbulent past. In 1834, the Governor of Tamsui (Tamsui being the historic capital of Taiwan), designated Jiang Xiu-luan, an immigrant from Guanzhou, as the leader of a land reclamation project in the area around current-day Beipu. The official wording used is “land reclamation” but perhaps “land acquisition” might have been more on the nose, since what Jiang and his men were actually doing was carving up the resident Aboriginals’ hunting grounds into neat parcels of land for use in agriculture and habitation. Of course, there were disputes and frequent fights, so sometime after 1835, a Guanyin idol was brought into the village so that residents could pray for peace and protection. At first, the deity was housed in a rough shrine, but in 1846, it was given a wooden building. The building has been updated several times over the years, and visitors who step into the incense-heavy courtyard now, are greeted by a beautiful, compact structure with many altars dedicated to all kinds of different gods.

I was intrigued by these wooden boxes that had been set up in front of the altar. Nine of them carried names of the nine villages that fall under the administrative control of Beipu Township, and the leftmost one is for “other” regions. Some of the boxes had flags in them, and the flags had pieces of paper bearing names attached to them. I can’t find any information about what these are for, but they don’t appear in other people’s photos of the temple, so I wonder if perhaps they’re related to some specific piece of annual temple bureaucracy.

Wherever you look, there are beautiful details to absorb. The left photo is some of the detailing on the pillars, and the right image shows a side-chamber full of prayer lights.

Some orange gremlins found on the service counter of Citian Temple.

When it was time to check in, I made my way towards Beipu Guest House, and before I could even find the door, I heard someone calling my name. It turned out to be my host for the night, and what a wonderfully friendly host she was! (I wish I’d asked for her name!) As she took me up to my room, she asked about my travels, and told me about the other guests who’d passed through on their own Raknus Selu walks. Hearing about all of these other visitors makes me feel hopeful that the Thousand Miles Trail Association’s goal of creating a healthy, self-sustaining walking tourism industry might just be taking root. My host said that last year, when the borders were still closed, there were more walkers passing through. But since some of those were ambassadors for the trail, perhaps there will be renewed ripples as they publicise their walks.

My host also gave me a few tips for places to visit, offered me homegrown bananas, explained how to make tea using the powder left in the communal kitchenette, and showed me how to use the spin drier in case I felt like washing my clothes (I did).

My room was big enough to accommodate three guests, and had a really comfortable, homey feel–red tiled floors and a floral bedsheet. It had everything I needed to enjoy a comfortable night’s sleep (I didn’t, but I think that should be blamed on the beer I drank rather than because of the room). After settling in, I headed back out to see some of the sights my host had mentioned.

My first priority was finding somewhere to try my hand at making lei cha. Lei cha (擂茶) is a type of traditional beverage made using numerous different ground-up ingredients. The name is quite literal, since the first character means “grind” in the Hakka language. As far as methods of consuming tea go, it is a unique one and something I’d never tried before visiting Beipu. Lots of stores over DIY lei cha grinding experiences. I asked my host if there were any she recommended, but she said no, it’s just personal preference really–do you want old-fashioned or modern, or maybe a particular flavour.

Before I go any further, it’s worth noting that prices seem to range between $320-$500 for the experience, and the minimum number of people is two (some stores advertise the per-person price, but even if you’re a single customer, you’ll have to pay for the to-person set). Unfortunately, Teresa had to work, so I was going to have to do all the hard work and all the drinking by myself.

I wandered around for a bit and checked on Google before deciding on Number 39 Beipu Lei Cha Store. The store claims to be the first place to “commercialise lei cha” (I’m not entirely sure what that means, since I’m sure there have been people buying and selling it for as long as it has existed). Scepticism aside, once you’ve settled on your store, the next thing to do is to pick which variety of lei cha you want to make. I wasn’t actually given a choice, they just sorted me out with the original flavour (which is good), but had I been able to choose, I think I would have selected the salty one.

When my set arrived, I was given a large, heavy bowl containing peanuts, sesame seeds and twists of dried tea. Another smaller bowl contained a powder containing roughly twenty ingredients. The store provided a card detailing everything that was in there, in total, I think there were nine types of beans, several grains and other things like gingko and yam. Included in the set was a dish of peanut-dusted mochi, and a snack platter with dried tofu, crackers and dried orange–you’ll need these to snack on, because the grinding process takes 40 to 50 minutes. The first step is to grind the peanuts, sesame seeds and dried green tree. There are three noticeable phases to this step. In the first, the ingredients crumble into a sandy, gravelly consistency. This is the most satisfying part because it’s very easy to see that you’re making progress. After that, the mixture becomes more of a powder and it seems entirely pointless to keep going, but if you push through, in the third phase, the oils in the nuts and sesame seeds start to emerge. At this point, one of the store aunties (there were many), came to check, and instructed me that it was time to add in the second bowl of powder. Another 10-15 minutes of grinding ensued, at the end of which, there was a thick almost-paste in the large bowl.

Once the mixture has achieved a consistency that pleased the aunties, they brought over a pot of water and showed me how to add a small amount of water to make a thick drink, then top it with puffed rice. Thankfully, I really liked it, because I had a whole lot of it to consume. In fact, I was so full of tea by the end that I didn’t even need dinner that night!

One of the beautiful backstreets (or not if you can’t get over Taiwan’s rather haphazard wire-work).

Not far from Citian Temple you can find a gorgeous European-style building. Modelled on European building aesthetics, the blend of Western and Asian styling makes it rather impressive. It was commissioned by Chiang A-hsin (姜阿新), one of the earlier residents to settle in Beipu and a businessman with fingers in several of the region’s business pies. His company, Zhudong Tea Co. was not just involved in the tea trade, but also in the sugar and timber industries. The Chiang family lost the house in 1965 when they filed for bankruptcy, but they were able to buy it back in 2012. By this point, the building had been listed as a national heritage site. The building saw a renewed surge of interest in 2022 after Taiwanese drama “Gold Leaf” was acquired by Netflix. The show, which was praised for being one of the first to bring the Hakka language to a global audience, centres on life in Chiang A-shin’s company and features scenes shot in Beipu.

As dusk settled on the small town, I decided to check out one more place before getting some rest. The woman at the guesthouse had told me that on Fridays, Beipu has a small night market. “Really, really small,” she clarified.

She wasn’t wrong. A handful of vendors set up their stalls at the end of Zhongshan Road that’s closest to Provincial Highway 3. I was tempted by the stinky tofu, but with a belly still full of lei cha, I decided to turn in for the night without a midnight snack.

GETTING THERE

Public transport:

- Getting to Zhudong – Take the Kuo-kuang bus number 1820 bound for Zhudong from Taipei Bus Station. The service currently leaves from the fourth floor of the bus station. Ride it for about ninety minutes and alight at Xiagongguan bus stop.

- Getting to Hengshan – If you plan to walk the whole of RSA25.1 in one go, you’ll need to start from Hengshan. The easiest way to get here is to take a train from Taipei to Hsinchu (fast services only stop here) Hsinchu North Station (local services would stop here), then transfer to a local train bound for Neiwan and alight at Hengshan.

- Getting back from Beipu quickly – Take the 5700 Taiwan Tourist Shuttle bus from Beipu Old Street to either Hsinchu HSR Station and catch a HSR service back to Taipei.

- Getting back from Beipu cheaply – Take the 5626 bus from Beipu Old Street to Zhudong High School. Transfer to the 1820 bus and ride it all the way back to Taipei.

Accommodation:

Staying in Hengshan – There aren’t many options in this area. If you want to camp, there are some basic campsites in the area (managed, not wild), but if you want a proper bed, it’s probably best to head up to Neiwan. I stayed in a little B&B in Neiwan the evening before walking this and caught the train back to the start of the trail.

- Name in Chinese: 山舍民宿

- Address: 312新竹縣橫山鄉內灣村內灣92號

- Contact: 035849988

- Cost: $1300 for a two-person room

Staying in Beipu – I stayed in Beipugo Guesthouse and would definitely recommend it. I paid $1200 for a three-person room with a bathroom that was private but which I actually had to leave the room to access (I could have chosen a room with a shower inside for $1500 per night). There’s a communal seating area on the ground floor and another on the upper floor where the rooms are. Guests are given towels, toiletries, a small kitchenette with cups and tea, and use of a spin drier.

- Name in Chinese: 北埔口民宿

- Address: 314新竹縣北埔鄉南興街168號北埔老街旁

- Contact: 035804121

- Cost: $1200-1500 (midweek)

Further reading: I’d recommend anyone hoping for a little background information on Beipu to check out this post from Josh Ellis’s site. And for those of you who are into history and can read Chinese, this is a good source of information on the subject.

RAKNUS SELU DAY 5 TRAIL MAP

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)

If you enjoy what I write and would like to help me pay for the cost of running this site or train tickets to the next trailhead, then feel free to throw a few dollars my way. You can find me on PayPal, Buy Me a Coffee or Ko-fi, (and if you’re curious about the difference between the three you can check my about page).