A wander through different periods of Kinmen’s history

Since so many of Kinmen’s attractions are just a little farther apart than most people want to walk, it seems that scooters or cars are by far the most popular ways to travel. But if you look at the map, there’s no reason (except the hot, hot sun) why you shouldn’t walk between places. This loop connects several spots that are more commonly visited on two or four wheels, and of course, while walking, you get to see lots of things you might otherwise miss if you were passing through at speed.

Distance: 7.7km

Time: This took us a very, very slow five hours.

Difficulty (regular Taiwan hiker): 2/10 – Road walking is tiring!

Difficulty (new Taiwan hiker): 3/10 – The hard surface is the most tiring element of this walk.

Total ascent: A little under 100m.

Water: We took 0.5L each (and a beer in Teresa’s case). There’s a convenience store at the start of the walk, and you can get refreshments from the little store at Zhaishan Tunnel too.

Shade: Almost none. I had an umbrella and suncream and was just about ok. My partner (who never usually burns), got a little fried by the Kinmen sun.

Mobile network: Clear throughout.

Enjoyment: My favourite part was walking through the old villages. But I also enjoyed being able to see so many different things on one walk. This route includes a short hiking trail, rural scenery, military relics, and pretty houses.

Other: It might be worth grabbing some type of snack from the convenience store before you set off.

Route type: Loop, but with the option to do a point-to-point walk if using public transport.

Permit: None needed.

Jump to the bottom of this post for a trail map and GPX file.

We began our loop from the bus stop on Zhushui Road just across from the 7-Eleven. If you don’t have water, make sure to get some here before you set off. This being a holiday, Teresa decided a beer would be the best choice of liquids for the walk. We headed northwest, with the old fort’s north gate on our right until turning left onto the last street before the end of the village in search of the west gate.

We arrived at the reconstructed west gate in under five minutes. It’s perhaps not too surprising that the original structures have almost all been lost to time since the walls were originally built in the 1300’s. The walls were built under the orders of Zhou Dexing (周德興), in order to better protect the army and citizens resident in the city. However, after the fortifications were breached twice, the military personnel stationed here were relocated to Jincheng (formerly Houopu), and Kinmen Fort became just a regular settlement. Then in 1949, ROC forces dismantled parts of the walls and used the stones to build their facilities.

From the rebuilt western gate, you can look out over the settlement of Shuitou and towards Little Kinmen.

If you keep heading southwestish along the same road, you’ll soon see the giant silver distillery silos of Kinmen Kaoliang’s Jincheng Factory.

The entrance to the factory is through the west gate. It seems that you can go inside, but by all accounts, there’s not much to do except buy kaoliang.

Looking back over a village pool towards the west gate and kaoliang distillery. There are many pools like this dotted throughout the old villages serving the dual purposes of aiding the positive flow of “qi” (at least, that’s what it does according to the principles of feng shui) and also providing a handy source of water in the event that one of the village’s tightly packed timber-framed buildings catches fire.

Right next to the pool, a statue of Ye Hua-cheng (葉華成) stands, leaning jauntily against a bottle of the kaoliang liquor that he used to produce and gazing at the main entrance of his old family home.

Since we were there already, we figured we may as well take a look inside the museum. It’s free to enter, the woman manning the entrance just asked that we sign in. She also said that if we wanted to watch the film, we just needed to ask her, but otherwise we were free to explore by ourselves.

The former residence of the Ye family is rather grand, and each of the rooms has been given over to explaining a different part of the kaoliang distilling process.

There’s a room showing you how the sorghum (or great millet) is treated after harvest, another shows how technology has changed, a third demonstrates traditional storage methods. However, the vast majority of the signs are only in Chinese, so if your Chinese reading is rusty, you might not learn much.

After no more than ten minutes, we made our way back to the entrance/exit, only to find that we had been locked in. We looked around for the attendant, but she had gone. Despite the fact that we were only her second visitors of the day, the woman had managed to entirely forget that we were in there and had gone for lunch. We were locked in. After deciding that the door we’d entered through must have been locked from the outside, we went to one of the other doors. All three had been open just minutes earlier, but two had ropes ages across them to prevent entry. Now all were shut. Thankfully, we were able to escape after sliding the bolts on the middle door.

Once we managed to break free, we continued up the road towards Wentai Tower (文臺寶塔). This is one of three similar structures built at different points across the island and was a kind of proto-lighthouse. This one was built in 1387.

Nearby, there’s a pavilion sheltering a large rock engraved with “虛江嘯臥”. Xu Jiang (who also went by the name of Yu Da-you), was a Ming dynasty battalion commander who was in the habit of visiting this location. According to English translations, it’s essentially the Ming dynasty equivalent of “Xu Jiang woz ‘ere” – except more literary and emotional by dint of its presentation, place in time, and vocabulary choice. Xu Jiang also added a couple of other engravings nearby, and subsequent commanders have also added carved characters of their own.

We walked down from the rock and past Wentai Tower, following the rural road out of the village. On the right, a dusty red section of what looks like the original walls remain. Weirdly, despite the information boards at every rebuilt landmark, there was nothing but a string of red flags to mark this spot.

From one unnamed road, we turned right at the first junction onto another. Here we passed a farmer and his cow just finishing up tilling the last row on their field as an Oriental magpie robin swooped in to pluck something tasty from the dirt.

Indeed, there were a number of cows tethered in the fields beside the road, and my sweet, sweet city girl wanted to greet each and every one of them. I dread to think how long it would take us to complete a walk along the trails around my parents’ village back home.

A gaping opening about fifty metres off the road caught our attention and we wandered over to have a look. Even once inside, the original intended use was unclear, although it was certainly military, and maybe something to do with munitions storage. The weirdest part weas the gigantic S-hooks. They were longer than my forearm, and were placed at almost every point of the octagonal structure.

Kinmen is riddled with places like this. In fact, the whole place kind of has this “should I be here?” weirdness about it. Roads feel like private farm tracks, and tourist attractions feel like they haven’t had a visitor in years.

Carrying on along the road, we turned right and then immediately right again into a small park that has been set up around another inscription. This one is known as the “Han Ying Yun Gen” inscription (so called because that is what is inscribed–inscription naming conventions are pretty straightforward around here). The Ming-era original has broken, so what you see by the pavilion is a duplicate of the one engraved by Zhu Yihai. Zhu was a Ming dynasty prince, and after the encroaching Ming forces caused the deaths and suicides of multiple family members, Zhu fled to Kinmen.

Head up the steps towards the pavilion to see the renovated inscription.

It looked as if it had only recently been given a new coat of paint when we were there. The signs for Liang Shan Guanzhi Hiking Trail were also very new. The trail starts right beside the clearing, and starts as a gentle, dusty climb.

There is a short section where the steps become steeper, but it is only a very, very short section.

At the top of the steps, take a right and keep heading slightly upwards. The highest point of this walk is a wooden viewing platform on the peak of Liang Hill.

Looking back in the direction we’d walked from, we could see Wentai Pagoda and looking more inland we saw the rather dry expanse of Gugang Lake with Gugand Tower clearly visible on the far bank.

Our arrival on the viewing platform coincided with the arrival of a tour-bus-worth of tourists, so we didn’t stay too long, and instead made our way down towards the second viewing platform.

Much of the trail is pretty open and there are some views over the coastline.

From the second viewing platform, the path heads gently down to join a track. Here we headed left until rejoining the road (where the tour bus was waiting to pick up the other walkers), and turned right to continue our journey.

Gugang Lake looked a rather sorry sight with most of the water drained, but I imagine that when full, the reflection of Gugang Tower’s red and green form must be quite impressive.

After walking through dusty farmland for a while, we came to this crossroads and took a right turn towards the Zhaishan Tunnels. The dust in the air-already a problem for Kinmen residents-was compounded by roadworks which were kicking up even more of the stuff.

When you start to notice a few tanks, that’s when you’ve almost arrived at the entrance to Zhaishan Tunnels.

There’s a little bit of a park area with more weaponry and a gift shop to pass through before you find yourself at the entrance to the tunnels. (Like literally every other historic or tourist site on the islands, this one is free to enter.)

By the doorway, there are shelves with yellow hard hats and signs asking all guests to wear one, but aside from one old chap, Teresa was the only helmet-wearer.

The path slopes gently down before heading through a doorway and down more steps towards the watery channel. All the while, classical music plays in the background-a recording taken from a festival organised by Taiwan’s Forestry Bureau (since the whole island has been designated as being Kinmen National Park, the Forestry Bureau is involved with a lot of things here).

The waterway was carved out of the granite bedrock in the 1960s and served as a secluded spot for military vessels to be stored and resupplied. The channels form a kind of “A” shape, and from where the steps join the water, you can walk left to one of the “A’s” feet, or right to walk up to it’s tip and then down to the further foot. The water is eerily still, and exceedingly clear. Close to one of the tunnel mouths (where it would have originally connected to the ocean before the channel got all silted up), we spotted a few fish darting around, but mostly the waters seemed uninhabited.

Back on the surface, you can take a brief detour to see the tunnel mouths from the outside. The path down to the water was flanked with these prickly pear cacti, many of which had erupted into pastel-yellow bloom.

The twin entrances are sheltered by jetties, the sound of the water echoing off of the face-to-face concrete surfaces.

We walked all the way to the end of the jetty to look out over the water and the coastline.

Looking back inland, the tunnel mouth is a gaping black hole, stopped up with more concrete and a sad little unreachable beach. It looks small in the photo, but when you’re there, it has an almost menacing presence. As we stood observing it, we spotted a goat standing tall on a rock and surveying the land.

Once we’d had our fill of the Zhaishan site, we headed back along the road to the crossroads where we had earlier taken a right turn. Instead of heading back the same way, we went straight over and headed towards the village of Gugang.

Along the way, we spotted a greater coucal. These are one of the coolest and weirdest birds we encountered on Kinmen. They can fly, but their preferred method of locomotion seems to be swaggering along on the ground.

Heading into the village was a good call. I’m not sure that this village is any more interesting or special than any other on Kinmen, but it’s such a pleasure to walk through this type of place. Buildings from various periods and in varying styles can be seen. From the crumbing old stone buildings.

We wandered through villages streets with low stone buildings ranged around communal pools.

Every time Teresa saw one of these pumps, she was drawn to it like a moth to a flame water.

Other communal areas are given over to shade-giving trees, benches and the omnipresent indications of the region’s extensive military past.

At every turn there are yet more examples of beautiful brickwork, terrific tiles, and a mishmash of different architectural flourishes.

This beautiful two-storey structure is Gugang School. There are quite a lot of old school buildings scattered across Kinmen and its smaller sibling, perhaps almost one per village. In fact, the place we stayed in for the second half of our Kinmen visit was right across from another of them.

Another building that caught out eye was this dilapidated structure to the left of the road. This is Dong Guang De Yang Lou (董光得洋樓).

The term “yanglou” is often translated as “mansion”, but there’s a little more to it than that. There are many “yanglou” scattered throughout the villages of Kinmen, most of which were built by wealthy merchants who had returned from foreign countries, and commissioned grand homes which fused western architectural flourishes with local ones. Each one that we saw was beautiful and unique. Some bore Ionic columns, others a mishmash of mismatched tilework, yet others had both plus the added detail of decorative fish-shaped downspouts. Some of the information written about this particular building online suggests that the person who commissioned it to be built was unlike other yanglou owners in that he managed to get rich without ever leaving Kinmen, so the details that can be seen are maybe just his imaginings of what a western-style mansion would look like.

We continued onwards, passing a school and some chickens before arriving at the point where we needed to take a left turn.

We found ourselves walking through the mostly single-storey Ming Yi Old Street (明遺老街) and past more old stone dwellings in varying states of habitation. Of those that had been abandoned, some had been left to the weeds and others repurposed as clothes-drying spaces or scooter parking.

At the far end of Mingyi Old Street, we found ourselves at Kinmen Fort’s reconstructed northern gate.

You can climb up it, so of course, I did (although I didn’t walk along the rebuilt section of wall because there’s nowhere to go at the far end). I ended the vantage point that it gave me to look into a small farm enclosure full of not-quite-peacefully coexisting goats and chickens.

Once down from the wall, we headed towards the temple in the lefthand photo, and that took us right back to where we’d started.

How to get there

As with literally everywhere on Kinmen, renting your own scooter is by far the easiest way to get to and from places, but this walk is served by a bus route.

Google maps address: We started close to Kinmen Fort’s western gate. In fact, we parked our scooter in an empty patch of space almost right next to the gate. From there we walked to Wentai Tower, up Liang Shan, then on towards Zhaishan Tunnel before looping back around to where we’d started.

Public transport: The Taiwan Tourist Shuttle A Route (between Shuitou and Zhaishan) and the 6A bus can be caught in Jincheng and will drop you off at the start (Mingyi Old Street or Jinmengcheng depending on which service you take). You can use an EasyCard to pay for the ride. If you feel tired when you reach Zhaishan Tunnel, the Taiwan Tourist Shuttle A Route will take you back from there to Jincheng.

Further reading: An article about Chiang Po-wei, a professor who’s interested in preserving Kinmen’s historic sites.

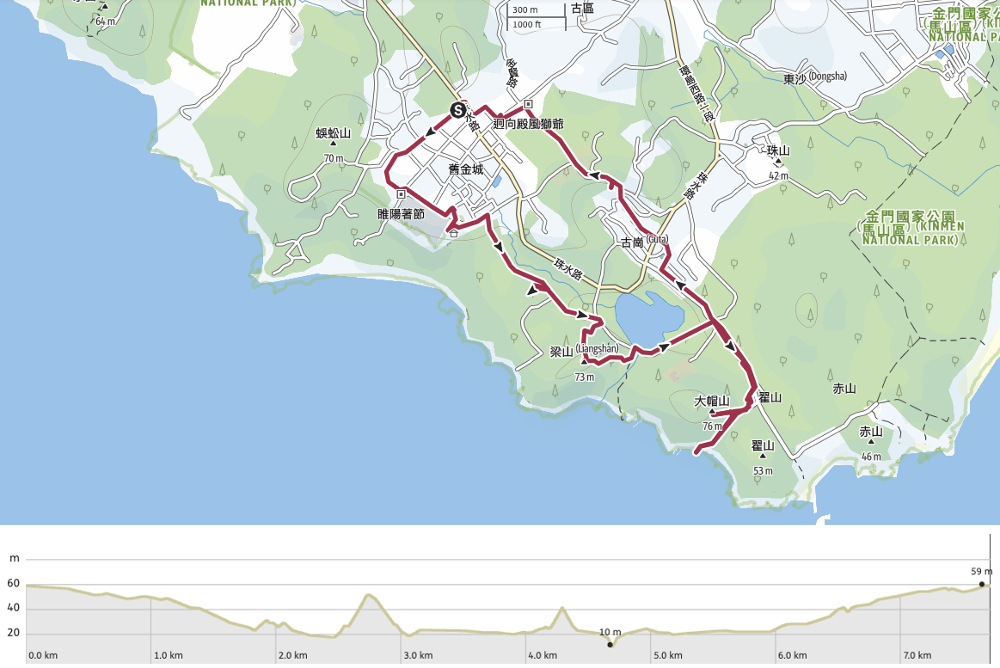

Kinmen Fort and Zhaishan Tunnel Trail Map

GPX file available here on Outdoor Active. (Account needed, but the free one works just fine.)

If you enjoy what I write and would like to help me pay for the cost of running this site or train tickets to the next trailhead, then feel free to throw a few dollars my way. You can find me on either PayPal or Buy Me a Coffee.